Bicycle use

In addition to making the city more pedestrian friendly and more sustainable, Curitiba planners have understood the need to also ease the transportation with man-powered means of transportation, like bicycles. Since 1972 and the beginning of the humanization of the city launched by the mayor Jaime Lerner, bikes have been considered as part of the planning solution. 1972 is a key moment in the history of Curitiba because it is the moment when the city begins to take the shape it has today, with its current guidelines of a city with a human-face and pedestrian friendly.

The answer came with the creation of bicycle lanes throughout the city (Figure 1). It has become a key element in Curitiba transportation system. These bicycle lanes were concentrated in the middle of the city, not its downtown, and spread around the universities and the botanical garden. Otherwise, it was going along the road 476 which can be compared to a freeway. Even if it was an improvement, the bicycle lanes were considered purely as a means of transportation and the convivial side was not taken in consideration. [1][2]

The answer came with the creation of bicycle lanes throughout the city (Figure 1). It has become a key element in Curitiba transportation system. These bicycle lanes were concentrated in the middle of the city, not its downtown, and spread around the universities and the botanical garden. Otherwise, it was going along the road 476 which can be compared to a freeway. Even if it was an improvement, the bicycle lanes were considered purely as a means of transportation and the convivial side was not taken in consideration. [1][2]

the 2013 Plan for Bicycles

Until 2013, Curitiba was equipped with 127 km of bicycle lanes. The Plano Director Cicloviario voted in 2013, and expected to enter into action in 2016, plans to add 300 km of bicycle lanes in the city. This plan is very interesting because it shows a comprehensive and coherent political commitment to improving the city bicycling system. The plan itself is a very bold decision, it allocates $90M to create a new mobility in the city, the goal is not only to add lanes, but really to change the way people move in the city. There is this double concern affirmed by the planners to develop the city in a sustainable way and to rehabilitate former space in order to make the whole city more efficient. Concretely, they are talking about principles such as creating bicycles lanes in sensitive areas: close to the river to ensure the preservation of the bank, next to former rails to avoid the development of unused land. It’s also a way to ensure that the land won’t decay overtime.

The plan is very accurate and has twelve points to make this change. The twelve plans are as follows:

The plan is very accurate and has twelve points to make this change. The twelve plans are as follows:

- 19.5 new km of bicycle lanes to link parts of the city

- Prioritizing bikes on 6.3 km of existing roads

- Creation of a bike rental system

- Improving already existing bicycle lanes (Figure 1)

- Creating 47 km of bicycle lanes to link 8 parks in Curitiba

- Finishing the ongoing projects relating to the bike infrastructures

- Adding 24.7 kms of bicycle lanes along main avenues and BRT routes

- Completion of a bicycle-friendly square in downtown

- Taking space on sidewalks to create 25 bike parking spots

- Creation of 20 parking stations close to bus stations to foster multimodal transportation

- Guide of cycling infrastructure: precisely scheduling the whole process

- Managing to pass a bill at the municipal level to force 5% of all parking space to be dedicated to bikes

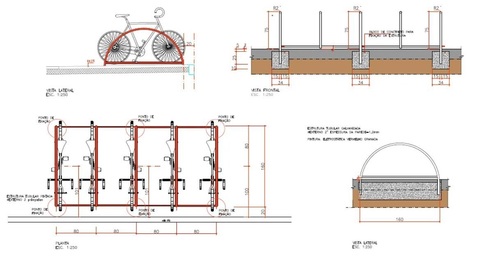

Figure 2. An Example of Bicycle Parking Used in Curitiba. Source: Prefecture of Curitiba

Figure 2. An Example of Bicycle Parking Used in Curitiba. Source: Prefecture of Curitiba

Curitiba doesn’t plan on eliminating all the other means of transportation, it is actually initiating a turn and easing the cohabitation of all the means of transportation. Also, this plan is not only about the lanes itself, it’s also about the infrastructures that allow people to park their bikes. Multimodal transportation means that people should be able to easily use two modes of transportation. Parking your bikes close to your bus stop is the best to incentivize you to use both of those means of transportation (Figure 2). To that extent, the plan organized the completion of 45 bicycle parking spots to support this evolution. [3]

From bicycles to other means of transportation

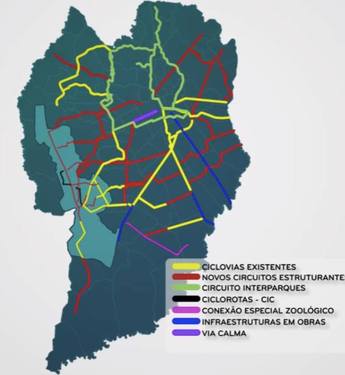

Figure 3. 'Via Calma' Bicycle Lane shown in purple. Source: Youtube; Plano Diretor Cicloviário de Curitiba

Figure 3. 'Via Calma' Bicycle Lane shown in purple. Source: Youtube; Plano Diretor Cicloviário de Curitiba

The first action that points out the will to ease cohabitation is the creation of the ‘via calma’. It means ‘calm lanes’ and they are dedicated to bicycles in an area where they can encounter other means of transportation such as buses or cars. The crucial difference in those lanes is that the speed limit is going to be decreased to 30km/h for the engined vehicles. To make sure that the law is enforced, speed bumps are going to be created every 60 meters to force the engine-powered means of transportation to decrease their speed. At the same time, bicycles will be in dedicated lanes separated by signs on the road. So, there won’t be a clear physical distinction but as the speed limit is decreased, the danger for bicyclists remains low. At the same time, it decreases the ambient noise downtown and make it more friendly for the pedestrians. This via calma is going to be 6.3 kilometers long and located in the north of the City in the Sete de Setembro avenue. Those 6.3 kms might seem small but they are implemented on one the main axis of the city, exactly in the center (Figure 3) with a lot of shops. It sends a strong message to the car owners and is the brightest manifestation of this desire to give back the city to its inhabitants. At the same time, those calm lanes won’t alter the efficiency of the bus system in Curitiba as the bus fast lanes are maintained in the area. [1] [3]

references

[1] Montaner, J. (1999). el modelo Curitiba: movilidad y espacios verdes, Ecología Política, 17

[2] Macedo, J. (2013). Planning a Sustainable City: The Making of Curitiba, Brazil. Journal of Planning History, 12(4), 334-353.

[3] Plano Diretor Cicloviário de Curitiba, Prefeitura de Curitiba, 2013

[2] Macedo, J. (2013). Planning a Sustainable City: The Making of Curitiba, Brazil. Journal of Planning History, 12(4), 334-353.

[3] Plano Diretor Cicloviário de Curitiba, Prefeitura de Curitiba, 2013