The History of Curitiba's Image: From the Smiling City to the City of All of Us

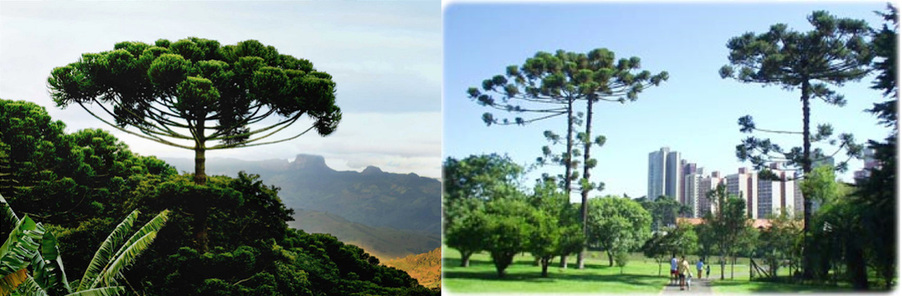

Figure 1. Araucaria Trees. Source: Wikipedia; Curitiba

Figure 1. Araucaria Trees. Source: Wikipedia; Curitiba

Curitiba calls itself “the city of all of us.” Several other nicknames have been given to Curitiba throughout the years. At the end of the 19th century, and into the early 20th century, European immigrants experienced great success as farmers in Curitiba's fertile land. When traveler's made their way through the city, they noticed these immigrant farmers smiling easily and often. Because of this, the travelers nicknamed Curitiba the “Smiling City.” [1] [2]

Curitiba's “Ecological Capital” - Bio City and Araucaria Tree

The amount of green space per resident of the city has grown extremely high. The decades between 1970 and 2013 saw the population of Curitiba nearly triple. During this time, the green space of the city has grown 128 times larger. Two programs that helped increase the green space of the city are for the reintroduction of native plants are called the “Bio City” and the “Araucaria Tree” programs. The Bio City program replaces exotic trees and plants with native ones. The Araucaria Tree program offers residents who are property owners up to a 50% reduction on their property taxes with the planting of native Araucaria trees (Figure 1). These trees can live up to 700 years, and grow to be 150 feet tall. Up to 5 trees can be planted, each for a 10% reduction on taxes. These factors and programs led to another nickname for the city, the “Ecological Capital.” [2]

Curitiba as The University City: City Planning and University Planning

The first Brazilian university, called Universidade Federal do Paraná, was established in 1912 in Curitiba. The first courses offered were in engineering, medicine, and law. Curitiba enjoys the lowest illiteracy rate among all the Brazilian state capitals. Also, there are more university graduates living in Curitiba than any other state capitol. These together led to Curitiba being known as “University City” within Brazil. [2]

Curitiba's “Ecological Capital” - Bio City and Araucaria Tree

The amount of green space per resident of the city has grown extremely high. The decades between 1970 and 2013 saw the population of Curitiba nearly triple. During this time, the green space of the city has grown 128 times larger. Two programs that helped increase the green space of the city are for the reintroduction of native plants are called the “Bio City” and the “Araucaria Tree” programs. The Bio City program replaces exotic trees and plants with native ones. The Araucaria Tree program offers residents who are property owners up to a 50% reduction on their property taxes with the planting of native Araucaria trees (Figure 1). These trees can live up to 700 years, and grow to be 150 feet tall. Up to 5 trees can be planted, each for a 10% reduction on taxes. These factors and programs led to another nickname for the city, the “Ecological Capital.” [2]

Curitiba as The University City: City Planning and University Planning

The first Brazilian university, called Universidade Federal do Paraná, was established in 1912 in Curitiba. The first courses offered were in engineering, medicine, and law. Curitiba enjoys the lowest illiteracy rate among all the Brazilian state capitals. Also, there are more university graduates living in Curitiba than any other state capitol. These together led to Curitiba being known as “University City” within Brazil. [2]

A city designed for its inhabitants

Over 40 years ago, in 1972, Curitiba made a leap forward in Brazilian planning history. The city created the first pedestrian street of the country in its own downtown, on the 15th of November Street which happened to be one of the busiest axis in the core of the city. The great challenge of making a city friendly toward its citizens is not an easy one and Curitiba planners and politicians came up with innovative ideas and bold solutions to make Curitiba one of the most pedestrian friendly city’s in the world today. Besides the pedestrian streets, one of the points of interest we have to focus on is the advent of green spaces. To incentivize pedestrians to be the main actors of the city obviously required the building of efficient public transportation. Beyond that the greatest challenge was making Curitiba a good place to live in. To give space and rest to its inhabitants, we can see that the building of green spaces had a core function, acting as a moral lung of the city, it has been about improving the experience of the city.

As a city is not about small isolated points of interests, we have to think of the green space policy as the starting point of a revolution that included a major shift in the way a pedestrian, or a biker can move through the city to go to those parks. The path followed by Curitiba in its pedestrian-friendly revolution began with an investment in a global pedestrian-friendly way of moving and a comprehensive plan for bikers. This is also part of the criticism of Curitiba: the fact that its sustainable and inhabitant-friendly development is completed only within its political limits, in isolation from the outer world. [4]

As a city is not about small isolated points of interests, we have to think of the green space policy as the starting point of a revolution that included a major shift in the way a pedestrian, or a biker can move through the city to go to those parks. The path followed by Curitiba in its pedestrian-friendly revolution began with an investment in a global pedestrian-friendly way of moving and a comprehensive plan for bikers. This is also part of the criticism of Curitiba: the fact that its sustainable and inhabitant-friendly development is completed only within its political limits, in isolation from the outer world. [4]

Pedestrians in curitiba

Figure 2. Rua XV de Novembro. Source: Wikipedia; Rua XV de Novembro

Figure 2. Rua XV de Novembro. Source: Wikipedia; Rua XV de Novembro

How did Curitiba become a city pedestrian friendly? We have to go back to one night of the Winter of 1972. A group of citizens, led by the architect and mayor of the city Jaime Lerner decided to remove the pavement and all the car facilities from the Calle de XV de Novembro (aka rua das Floras) in order to take back space from the automobiles (Figure 2). This street is located in downtown Curitiba, exactly at the core of the city. At the beginning, the initiative had been seriously criticized by the shop owners but eventually, it happened to dramatically increase the foot traffic and consequently, the amount of customers. This initiative was a success and was the first real sign of the time of greatest physical transformation for the city that Lerner was asking for. There was no legal basis, no special organization, just a general will to change the course of history in the city. We can see here the need for the inhabitants to really make the city theirs. It’s a real disruption from the top-bottom tradition in urban planning. It was a public initiative. [3]

This event can be seen as the starting point and the founding principle of Curitiba pedestrian friendly orientation. It had a real impact and the city needed to reinvent itself for pedestrians. The street was legally pedestrianized in November 1972, The direct legacy of this initiative can be seen in the rua 24 hora (24/7 street). This is an axis 2,000 feet West from the Calle de XV de Novembro dedicated to pedestrians in which, whenever during the day or the night, the inhabitants can find open grocery stores, restaurants, and bars. This move is crucial to understand that more than making a city efficient, there was a public demand for making the city more convivial. [4]

This event can be seen as the starting point and the founding principle of Curitiba pedestrian friendly orientation. It had a real impact and the city needed to reinvent itself for pedestrians. The street was legally pedestrianized in November 1972, The direct legacy of this initiative can be seen in the rua 24 hora (24/7 street). This is an axis 2,000 feet West from the Calle de XV de Novembro dedicated to pedestrians in which, whenever during the day or the night, the inhabitants can find open grocery stores, restaurants, and bars. This move is crucial to understand that more than making a city efficient, there was a public demand for making the city more convivial. [4]

Recreational use of the bicycle lanes

Another key project of the plan is called the “interparques” which means the inter-green space. It is planned to be 47 kilometers long. This is the main innovation of this program in terms of length in the northern part of the city. The goal of this project is to link the 8 main green spaces in the city, namely the UNILIVRE, the Botanical garden, the Zoo and the Opera. Those places constitute themselves recreational areas: the botanical garden is 17.7 acres and hosts many of the animal species of the region. Creating 47 kilometers of bike lane is very ambitious and this ambition was addressing two problems. The first was to make the city more practical to cross using bikes, the second was the lack of good roads for recreational use in Curitiba. The idea is to create a society that can evolve in a sustainable and friendly atmosphere. The emphasis put on this axis relies on the fact that this is the busiest axis for runners and bikers. Most of this project has already been done and now there are only 5.5 kilometers to refurbish to complete the whole plan. [5]

Quality of Life: People First in Planning

Figure 3. A bus-classroom. PBS; Curitiba

Figure 3. A bus-classroom. PBS; Curitiba

Part of what makes Curitiba a great international model for sustainable development is mainly due to the fact that people are put first in planning. The quality of life for all of the residents, and how to improve it, is what is addressed first with all urban planning in the metropolitan area. A focus on cultural heritage, social programs, and environmental programs have been the underlying goal even when the city was experiencing explosive population growth. [1]

Open University for the Environment

One of the programs offered by the city is called the 'Open University for the Environment.' This program offers people in the most common jobs, short, practical courses about how these jobs can have an affect on the environment. Some examples of the jobs covered in this program are homemakers, shopkeepers, or building superintendents. This program also offers the prerequisites for such things as earning a taxi driver's license. [6]

Mobile Classrooms and Apprenticeships

Former Mayor Jaime Lerner created a plan to redevelop former city buses that were no longer suitable for the bus rapid transit into mobile classrooms (Figure 3). These classrooms offer courses for adults in how to become typists, seamstresses, auto mechanics and electricians in order to learn a marketable skill and find employment. Another program offers young people who have no other option and who have turned to the streets apprenticeships in programs where they work part time. Payment for these apprenticeships is in the form of meals, stipends, and also schooling. [7]

Incentives and Systems for Encouraging Beneficial Behavior

Another way Curitiba keeps people first is with an innovative system that allows for the provision to any citizen that asks for it, the public information about any piece of land within the city and building potential of that parcel. This helps cut through bureaucracy that in other cities can be extremely time consuming. This ease of access to the land information helps avoid land speculation, and also helps keep in alignment the city's budget, because one of the main incomes for the city is property taxes. [6]

Historic Building Preservation

Along with this easy to access information is the ability for land owners of buildings to 'purchase' special permits that allow the construction of up to 2 additional floors to the top of the building beyond what the zoning of the area calls for. The 'purchase' price can be paid with either cash or gifted land. This payment is then used to fund additional low income housing. Also, owners of historic buildings in Curitiba are allowed to transfer the building potential of their land to another plot of land in the city. This allows for just compensation to the land owner and keeps the historic building preserved. [6]

Children’s Programs

Several programs for children are provided for with city funds. Over 12,000 children are served up to 4 meals a day through many of the day care centers in Curitiba. There is a special phone number and system in place called 'SOS Children', and is in case a child is in any type of danger or in a harmful situation. Also, children in low income families are able to take on a part time job in the 'Paperboy/Papergirl' program, which is a newspaper delivery program. [6]

Open University for the Environment

One of the programs offered by the city is called the 'Open University for the Environment.' This program offers people in the most common jobs, short, practical courses about how these jobs can have an affect on the environment. Some examples of the jobs covered in this program are homemakers, shopkeepers, or building superintendents. This program also offers the prerequisites for such things as earning a taxi driver's license. [6]

Mobile Classrooms and Apprenticeships

Former Mayor Jaime Lerner created a plan to redevelop former city buses that were no longer suitable for the bus rapid transit into mobile classrooms (Figure 3). These classrooms offer courses for adults in how to become typists, seamstresses, auto mechanics and electricians in order to learn a marketable skill and find employment. Another program offers young people who have no other option and who have turned to the streets apprenticeships in programs where they work part time. Payment for these apprenticeships is in the form of meals, stipends, and also schooling. [7]

Incentives and Systems for Encouraging Beneficial Behavior

Another way Curitiba keeps people first is with an innovative system that allows for the provision to any citizen that asks for it, the public information about any piece of land within the city and building potential of that parcel. This helps cut through bureaucracy that in other cities can be extremely time consuming. This ease of access to the land information helps avoid land speculation, and also helps keep in alignment the city's budget, because one of the main incomes for the city is property taxes. [6]

Historic Building Preservation

Along with this easy to access information is the ability for land owners of buildings to 'purchase' special permits that allow the construction of up to 2 additional floors to the top of the building beyond what the zoning of the area calls for. The 'purchase' price can be paid with either cash or gifted land. This payment is then used to fund additional low income housing. Also, owners of historic buildings in Curitiba are allowed to transfer the building potential of their land to another plot of land in the city. This allows for just compensation to the land owner and keeps the historic building preserved. [6]

Children’s Programs

Several programs for children are provided for with city funds. Over 12,000 children are served up to 4 meals a day through many of the day care centers in Curitiba. There is a special phone number and system in place called 'SOS Children', and is in case a child is in any type of danger or in a harmful situation. Also, children in low income families are able to take on a part time job in the 'Paperboy/Papergirl' program, which is a newspaper delivery program. [6]

Figure 4. The fundaçao cultural de Curitiba is a key element in preserving the city legacy. Source: Arquivometal CWB

Figure 4. The fundaçao cultural de Curitiba is a key element in preserving the city legacy. Source: Arquivometal CWB

Cultural Programs

A large part of the planning and development of Curitiba has always been the integration of the variety of cultures that have come together to form the city. In the same year that the CIC was developed, the Fundação Culturel de Curitiba was formed (Figure 4). This foundation is used to facilitate the development of the culture and promote cultural events within the city. The Fundação Culturel de Curitiba employs a specialized staff that work at over 150 cultural event sites planned throughout the city. Over 50 buildings are specifically used for cultural events. Cultural centers, museums, theaters, and working studios are just some of the offerings for citizens of Curitiba. Part of Jaime Lerner's plan in the 1970's included historic preservation. However, instead of preserving specific buildings only, Curitiba decided to preserve an entire historical district. This method of preservation soon followed throughout the country. The historical sector is now a tourist draw for the city. The first public space in Brazil to be preserved for marionette and puppet shows is called the Piá Theater, and is located in the historical sector.

A large part of the planning and development of Curitiba has always been the integration of the variety of cultures that have come together to form the city. In the same year that the CIC was developed, the Fundação Culturel de Curitiba was formed (Figure 4). This foundation is used to facilitate the development of the culture and promote cultural events within the city. The Fundação Culturel de Curitiba employs a specialized staff that work at over 150 cultural event sites planned throughout the city. Over 50 buildings are specifically used for cultural events. Cultural centers, museums, theaters, and working studios are just some of the offerings for citizens of Curitiba. Part of Jaime Lerner's plan in the 1970's included historic preservation. However, instead of preserving specific buildings only, Curitiba decided to preserve an entire historical district. This method of preservation soon followed throughout the country. The historical sector is now a tourist draw for the city. The first public space in Brazil to be preserved for marionette and puppet shows is called the Piá Theater, and is located in the historical sector.

Poverty

Curitiba's reputation in Brazil for an above average quality of life has had an unfortunate side effect. Beginning in the 1960's, the city started seeing slums develop, called favelas, because of the rapid influx of rural populations. Estimates from around the year 2000 deduced about 10 to 15 percent of Curitiba's population lived in the favelas. Several counts over the years have shown the increasing numbers of informal dwellings in and around the city. A field count done in 1989 found nearly 25,000 housing units that were considered substandard. In 1997, throughout 245 separate favelas, there was an estimated 52,716 families living in these dwellings. In 2002, there were 330 favelas counted, and it was estimated there were 58,530 families within Curitiba living in these informal houses. Lack of basic sewage infrastructure is a serious problem among the favelas. As of the 2000 Census, 7.5% of houses had no effective means of sewage disposal, and because of this, sewage was entering storm drains and open ditches. While, overall, Curitiba's residents enjoy the highest living standards, the number of people living in poverty as of 2000 was nearly 143,000 people. The 2000 Census shows that Curitiba's mean monthly income is nearly four times the national average, and is twice the average of the rest of the state. Even with these better than average incomes, there are still wide disparities in income distribution within the city. [4] [8] [9]

REFERENCES

[1] MacLeod, K. (2002). Curitiba: Orienting Urban Planning to Sustainability. International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives, Case Study 77. ICLEI-Cananda.

[2] Moore, S. (2007). Alternative Routes to the Sustainable City: Austin, Curitiba, and Frankfurt. Lexington Books.

[3] Montaner, J. (1999). el modelo Curitiba: movilidad y espacios verdes, Ecología Política, 17

[4] Macedo, J. (2013). Planning a Sustainable City: The Making of Curitiba, Brazil. Journal of Planning History, 12(4), 334-353.

[5] History of Curitiba - Prefeitura de Curitiba. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.curitiba.pr.gov.br/idioma/ingles/historia

[6] Rabinovitch, J. (1996). A Success Story of Urban Planning: Curitiba. Scientific American). (Reprinted in Cities Built for People, U. Kirdar, 1997, New York: United Nations)

[7] Brooke, James. (1992, May 7). "Curitiba Journal: The Road To Rio." The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com

[8] Macedo, J. (2004). City Profile: Curitiba. Cities, 21(6), 537-549.

[9] Higher Education in Regional and City Development. (2011). State of Parana, Brazil. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?isbn=9264089020

[2] Moore, S. (2007). Alternative Routes to the Sustainable City: Austin, Curitiba, and Frankfurt. Lexington Books.

[3] Montaner, J. (1999). el modelo Curitiba: movilidad y espacios verdes, Ecología Política, 17

[4] Macedo, J. (2013). Planning a Sustainable City: The Making of Curitiba, Brazil. Journal of Planning History, 12(4), 334-353.

[5] History of Curitiba - Prefeitura de Curitiba. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.curitiba.pr.gov.br/idioma/ingles/historia

[6] Rabinovitch, J. (1996). A Success Story of Urban Planning: Curitiba. Scientific American). (Reprinted in Cities Built for People, U. Kirdar, 1997, New York: United Nations)

[7] Brooke, James. (1992, May 7). "Curitiba Journal: The Road To Rio." The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com

[8] Macedo, J. (2004). City Profile: Curitiba. Cities, 21(6), 537-549.

[9] Higher Education in Regional and City Development. (2011). State of Parana, Brazil. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?isbn=9264089020