The early days (1693-1990s)

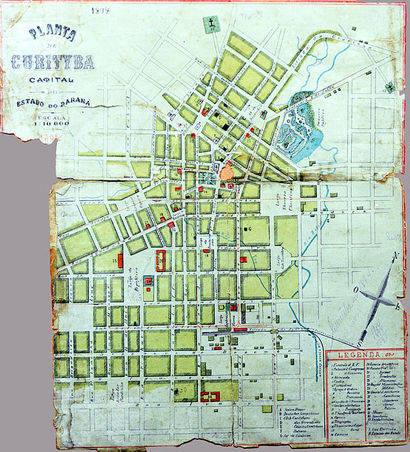

Figure 1. 1894 Map of Curitiba Planning. Source: Wikipedia; Curitiba

Figure 1. 1894 Map of Curitiba Planning. Source: Wikipedia; Curitiba

Curitiba is the capital city of the state of Paraná and is also its largest city. Curitiba is located within Brazil and has been growing rapidly over the course of the last half century. The earliest known inception date for the city of Curitiba is March 29th, 1693 which is when the City Council was formed. The original settlers of the city were Portuguese and Spanish immigrants that were predominantly cattle-farmers. For most of its early years, Curitiba’s agriculture consisted of subsistence farming while its economy was centered on mineral extraction (Figure 1).

Curitiba’s agrarian economy was also bolstered by the ‘tropeiros’ that visited and settled in the region during the winter periods. These cattle drivers “traveled with their herds from Viamao…to the fair in Sorocaba, in the state of São Paulo.” [1] While the ‘tropeiros’ stayed in Curitiba, they traded with local merchants and helped to establish Curitiba as an intermediary trading post for different kinds of minerals, livestock, agricultural goods, and other miscellaneous items. [1]

While this was the first economic boom that helped Curitiba start to grow as a major city in Brazil, there were three other points of economic success that occurred prior to the 20th century; two of which were happening at relatively simultaneous points to each other in the 19th century. The use of the maté plant for tea and wood for the development of the railroad were highly influential in propagating Curitiba’s economy. The maté plant was used to create a bitter tea called ‘chimarrão’ which became one of Curitiba’s largest exports during the 19th century. It became so successful that the ‘Maté Barons’ who controlled the companies built mansions in Curitiba that are still reserved as historic sites today. [1]

From 1880-1885, the city enhanced its connectivity to other industrial cities through the development of the Paranaguá-Curitiba railroad. It also served to connect Curitiba to the ocean. Having these connections helped the city to grow immensely over the next 60 years to a population of roughly 140,000 by 1940. During this time migrant workers in Curitiba began to be replaced by German, Italian, Japanese, Ukrainian and other various European immigrants which helped to expand the city’s economic and cultural development. The sharpest population increase was during the 1950s after the development and implementation of the Agache Plan in 1943. The Agache Plan was Curitiba’s first comprehensive plan and was developed in anticipation of a post-World War II building boom. [2]

Curitiba’s agrarian economy was also bolstered by the ‘tropeiros’ that visited and settled in the region during the winter periods. These cattle drivers “traveled with their herds from Viamao…to the fair in Sorocaba, in the state of São Paulo.” [1] While the ‘tropeiros’ stayed in Curitiba, they traded with local merchants and helped to establish Curitiba as an intermediary trading post for different kinds of minerals, livestock, agricultural goods, and other miscellaneous items. [1]

While this was the first economic boom that helped Curitiba start to grow as a major city in Brazil, there were three other points of economic success that occurred prior to the 20th century; two of which were happening at relatively simultaneous points to each other in the 19th century. The use of the maté plant for tea and wood for the development of the railroad were highly influential in propagating Curitiba’s economy. The maté plant was used to create a bitter tea called ‘chimarrão’ which became one of Curitiba’s largest exports during the 19th century. It became so successful that the ‘Maté Barons’ who controlled the companies built mansions in Curitiba that are still reserved as historic sites today. [1]

From 1880-1885, the city enhanced its connectivity to other industrial cities through the development of the Paranaguá-Curitiba railroad. It also served to connect Curitiba to the ocean. Having these connections helped the city to grow immensely over the next 60 years to a population of roughly 140,000 by 1940. During this time migrant workers in Curitiba began to be replaced by German, Italian, Japanese, Ukrainian and other various European immigrants which helped to expand the city’s economic and cultural development. The sharpest population increase was during the 1950s after the development and implementation of the Agache Plan in 1943. The Agache Plan was Curitiba’s first comprehensive plan and was developed in anticipation of a post-World War II building boom. [2]

Economy

Figure 2. CIC, 1970s. Source: Agencia Curitiba

Figure 2. CIC, 1970s. Source: Agencia Curitiba

The Cidade Industrial de Curitiba

The Cidade Industrial de Curitiba, or CIC, was developed in 1973 (Figure 2) as an economic project to create an industrial zone for the city of Curitiba. The area is located outside of the city, and was a designated spot for new factories to be built, but also a place for industries within the city borders to relocate. The CIC is located approximately 8km west of downtown Curitiba. Over 1200 factories occupy the space now, and provide nearly 30,000 jobs. These factory jobs provide nearly 1/5 of the city's jobs, either directly or indirectly. Also, no polluting industries are allowed in the CIC. With Curitiba being marketed as a successful urban planned area, many corporations were persuaded into relocating their factories there. A provision in the planning of the CIC was that low income housing be built to provide affordable housing and ease of access to the jobs provided by the CIC. The change from an agricultural processing center to an industrial center throughout the 70's and 80's was partly caused by the greater than 5% population increase per year during that time frame. The CIC was developed with the infrastructure in mind to accommodate transportation, housing, and leisure activities that were connected to the city. Even though the planning of Curitiba included aspects regarding the growth of industry, the explosion of the population was too much for the labor market to handle, and left many families in desperate financial need. Nearly 20% of the population was living below the poverty line as of 1999. The industry's that had relocated to Curitiba typically brought their own labor force with them, so there were not enough jobs to meet the demand for work. Few jobs were offered to the local population, but they typically required skills or education that the rural immigrants did not have. Today, Curitiba is highly involved in the automotive industry and Volvo, Renault and Audi-VW each have factories in the industrial area of the city. Nearly half the GDP of the state of Parana is due to the industries within Curitiba. [3] [4] [5] [6] [7]

Demographic Changes

The 1872 population count in Curitiba was just under 13,000 residents. The first official Census of Brazil, which was in 1890, counted about 53,000 residents. Between 1896 and 1914, Curitiba gained around 56,000 more immigrants from Asia, the Middle East, more from Europe, and from other states within Brazil. Between 1900 and 1950, the population shot up to nearly 180,000 people. Another near doubling of the population occurred between 1950 and 1960 to over 300,000 residents. The Black Frost of 1975 caused a massive migration in excess of 1 million people out of rural areas and into Curitiba and surrounding Brazilian states. The urban population doubled during the 1970's due to the industrialization that occurred. This doubling was the highest rate of growth in the capitals during that time, even though the state of Paraná experienced the smallest growth out of all the Brazilian states. Migrants, which are classified as anyone who has lived in the city less than 10 years, constituted nearly a third of the population in the 1980's. There are about 3.35 people in the average household in Curitiba. The 2010 census accounted for 1.8 million people in Curitiba. Today, Curitiba is home to nearly a third of Paraná's population. [5] [7] [8]

The Cidade Industrial de Curitiba, or CIC, was developed in 1973 (Figure 2) as an economic project to create an industrial zone for the city of Curitiba. The area is located outside of the city, and was a designated spot for new factories to be built, but also a place for industries within the city borders to relocate. The CIC is located approximately 8km west of downtown Curitiba. Over 1200 factories occupy the space now, and provide nearly 30,000 jobs. These factory jobs provide nearly 1/5 of the city's jobs, either directly or indirectly. Also, no polluting industries are allowed in the CIC. With Curitiba being marketed as a successful urban planned area, many corporations were persuaded into relocating their factories there. A provision in the planning of the CIC was that low income housing be built to provide affordable housing and ease of access to the jobs provided by the CIC. The change from an agricultural processing center to an industrial center throughout the 70's and 80's was partly caused by the greater than 5% population increase per year during that time frame. The CIC was developed with the infrastructure in mind to accommodate transportation, housing, and leisure activities that were connected to the city. Even though the planning of Curitiba included aspects regarding the growth of industry, the explosion of the population was too much for the labor market to handle, and left many families in desperate financial need. Nearly 20% of the population was living below the poverty line as of 1999. The industry's that had relocated to Curitiba typically brought their own labor force with them, so there were not enough jobs to meet the demand for work. Few jobs were offered to the local population, but they typically required skills or education that the rural immigrants did not have. Today, Curitiba is highly involved in the automotive industry and Volvo, Renault and Audi-VW each have factories in the industrial area of the city. Nearly half the GDP of the state of Parana is due to the industries within Curitiba. [3] [4] [5] [6] [7]

Demographic Changes

The 1872 population count in Curitiba was just under 13,000 residents. The first official Census of Brazil, which was in 1890, counted about 53,000 residents. Between 1896 and 1914, Curitiba gained around 56,000 more immigrants from Asia, the Middle East, more from Europe, and from other states within Brazil. Between 1900 and 1950, the population shot up to nearly 180,000 people. Another near doubling of the population occurred between 1950 and 1960 to over 300,000 residents. The Black Frost of 1975 caused a massive migration in excess of 1 million people out of rural areas and into Curitiba and surrounding Brazilian states. The urban population doubled during the 1970's due to the industrialization that occurred. This doubling was the highest rate of growth in the capitals during that time, even though the state of Paraná experienced the smallest growth out of all the Brazilian states. Migrants, which are classified as anyone who has lived in the city less than 10 years, constituted nearly a third of the population in the 1980's. There are about 3.35 people in the average household in Curitiba. The 2010 census accounted for 1.8 million people in Curitiba. Today, Curitiba is home to nearly a third of Paraná's population. [5] [7] [8]

The agache Plan

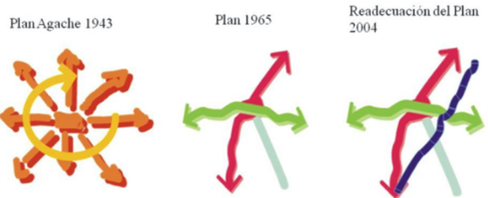

Figure 3. Curitiba's Plans. Source: Codatu; Curitiba

Figure 3. Curitiba's Plans. Source: Codatu; Curitiba

As more and more immigrants began to move into the city coupled with in-migrants from the rural parts of Paraná in search of economic opportunity during and after World War II, many local officials feared that Curitiba would become a sprawling metropolis. As they didn’t want Curitiba to turn out like neighboring São Paulo, planners got together and figured out three long term goals for the city of Curitiba to focus on: “future growth should be channeled along well-defined linear corridors; transportation investments and land-use management to direct growth; and planning for the full motorization of the city.” In order to accomplish these goals, Curitiba’s local officials instituted the Agache Plan (Figure 3). [9]

The Agache Plan was developed by a French urban planner by the name of Alfred Agache in 1943. One of main prospects within Agache’s plan called for the full motorization of the city and that “grand boulevards radiating from the central core” were necessary to accommodate the expected increases in automobile traffic. The Agache Plan was influenced by the French Haussman tradition of monumental public works projects and called for massive infrastructure investments that would level most of Curitiba’s oldest historical buildings.

Another proponent of the plan was the connection of downtown to the rest of the city through rings of concentric circles. Unlike modern Curitiba, the city was planning on expanding the interconnectedness of the city through modes of access with automobiles, but was not thinking of doing so with the use of public transit through the Agache Plan. The goal here was to attract automobile manufacturing industries to Curitiba so that the city could become globally competitive and with the onset of cheap post-World War II gas prices, it seemed very possible. Unfortunately, the largest problem that Curitiba faced was the fact that it did not have the necessary funds to actually implement the plan. However, the Agache plan served to raise public awareness about the future growth of Curitiba during the post-World War II expansion era. The Agache Plan served to promote the necessity of interconnection between the inner and outer city in Curitiba’s built environment. [9]

The Agache Plan was developed by a French urban planner by the name of Alfred Agache in 1943. One of main prospects within Agache’s plan called for the full motorization of the city and that “grand boulevards radiating from the central core” were necessary to accommodate the expected increases in automobile traffic. The Agache Plan was influenced by the French Haussman tradition of monumental public works projects and called for massive infrastructure investments that would level most of Curitiba’s oldest historical buildings.

Another proponent of the plan was the connection of downtown to the rest of the city through rings of concentric circles. Unlike modern Curitiba, the city was planning on expanding the interconnectedness of the city through modes of access with automobiles, but was not thinking of doing so with the use of public transit through the Agache Plan. The goal here was to attract automobile manufacturing industries to Curitiba so that the city could become globally competitive and with the onset of cheap post-World War II gas prices, it seemed very possible. Unfortunately, the largest problem that Curitiba faced was the fact that it did not have the necessary funds to actually implement the plan. However, the Agache plan served to raise public awareness about the future growth of Curitiba during the post-World War II expansion era. The Agache Plan served to promote the necessity of interconnection between the inner and outer city in Curitiba’s built environment. [9]

The 1965 master plan

In need of a plan to properly develop the city, civic leaders put together a competition that allowed local planners and architects to compete amongst each other by allowing them to propose plans for the future growth of Curitiba. The result of the competition was the 1965 Master Plan for the city of Curitiba. The new plan turned away from the previous plans design of a city layered by concentric circles in favor of a more concentrated and controlled form of growth along designated axes. The design was instead supposed to be linear allowing for growth to take place along designated roots in order to prevent the city from becoming a sprawling metropolis like São Paulo (Figure 3). [9]

Growth along these linear corridors would be for high-density development while allowing for less concentrated development to occur alongside. Next to the axes are 4 types of zones: ZR 4, ZR 3, ZR 2, and ZR 1 zones. ZR 4 and ZR 3 have a mix of residential, office, and housing spaces but as one travels further from the axes the concentration begins to taper off to ZR 2 & 1 which is mostly single-family detached homes. [9]

“By the 1960s, central Curitiba was showing signs of overcrowding and traffic congestion.” (p. 269) As compared to the previous plan that focused on trying to encourage automobiles to travel through the city center in order to make cross-town trips, the Master Plan called for downtown Curitiba and its historic center to be closed off. Instead, the city would wean itself off the dependence on low-occupancy vehicles and shift its attention to mass transit and high-occupancy vehicles. [9]

In essence, the Master Plan removed cars from the equation and focused on meeting the transportation needs of the people. Another greater function of the Master Plan was the interconnectedness of the further out zones to the axes through transit. Rather than creating multiple overlapping avenues for driving into the central city and causing greater congestion through interactions with single-occupancy vehicles and buses or other types of mass transit, express lines were put in that connected directly with axes. Here the main transit lines would serve to form the backbone of the city with the express lines serving as branches. This created an integrated transit network that planners and officials called the “trinary road system” which they hoped would lead to “more balanced, bidirectional traffic patterns” which would inevitably help sustain the transit system and make mass transit a viable alternative to driving a single occupancy vehicle. [9]

The most important part of this process was that careful consideration for the future growth of the city was driven by land-use decisions in terms of where city planners wanted the city to grow, namely, the north-south and east-west transit corridors. Subsequently, transportation planning came in afterwards to reinforce these growth expectations and prevent the original plan from changing. [9]

Growth along these linear corridors would be for high-density development while allowing for less concentrated development to occur alongside. Next to the axes are 4 types of zones: ZR 4, ZR 3, ZR 2, and ZR 1 zones. ZR 4 and ZR 3 have a mix of residential, office, and housing spaces but as one travels further from the axes the concentration begins to taper off to ZR 2 & 1 which is mostly single-family detached homes. [9]

“By the 1960s, central Curitiba was showing signs of overcrowding and traffic congestion.” (p. 269) As compared to the previous plan that focused on trying to encourage automobiles to travel through the city center in order to make cross-town trips, the Master Plan called for downtown Curitiba and its historic center to be closed off. Instead, the city would wean itself off the dependence on low-occupancy vehicles and shift its attention to mass transit and high-occupancy vehicles. [9]

In essence, the Master Plan removed cars from the equation and focused on meeting the transportation needs of the people. Another greater function of the Master Plan was the interconnectedness of the further out zones to the axes through transit. Rather than creating multiple overlapping avenues for driving into the central city and causing greater congestion through interactions with single-occupancy vehicles and buses or other types of mass transit, express lines were put in that connected directly with axes. Here the main transit lines would serve to form the backbone of the city with the express lines serving as branches. This created an integrated transit network that planners and officials called the “trinary road system” which they hoped would lead to “more balanced, bidirectional traffic patterns” which would inevitably help sustain the transit system and make mass transit a viable alternative to driving a single occupancy vehicle. [9]

The most important part of this process was that careful consideration for the future growth of the city was driven by land-use decisions in terms of where city planners wanted the city to grow, namely, the north-south and east-west transit corridors. Subsequently, transportation planning came in afterwards to reinforce these growth expectations and prevent the original plan from changing. [9]

Updating the bus transit system

By the mid-1980s, the transit system that Curitiba developed became extremely successful. The only problem, however, was that too many people were riding the express buses and they weren’t able to keep up with the demand which resulted in frequent schedule delays. “Convoys of articulated buses were hauling close to 10,000 passengers per lane per hour,” which “begin to match the loads of many fixed-guideway rail systems.” In order to combat overcrowded buses, developers came up with the idea of the Direct Line bus service that are located along the axes of the city. These buses have fewer stops and allow for those making longer work trips on a daily basis to get to work faster. This rail has highly complimented the transit system that Curitiba already had in place by providing a greater ability to move quickly within the city to different points of interest as “nearly one-third of Curitibanos live within an easy walk of the busway.” The most beneficial aspect of the Direct Line bus service is that it has allowed planners to continue to control development and allow for greater movement within the city and into the 21st century. [9]

Jaime Lerner and reclaiming downtown curitiba

Figure 4. Downtown Curitiba. Source: INF UFPR

Figure 4. Downtown Curitiba. Source: INF UFPR

In 1971, Jaime Lerner was elected to be the mayor of Curitiba. He became one of the most influential members in implementing the Master Plan of 1965 through his experience with the Curitiba Research and Urban Planning Institute (or the Instituto de Pesquisa e Planejamento Urbano de Curitiba (IPPUC). To do this, Lerner and the IPPUC organized passive aggressive protests to reclaim the downtown streets by occupying them with civilians and children to prevent cars from entering the area.

While protesters prevented cars from coming in, others destroyed the roadways behind them using pickaxes so the roads would be too damaged to drive on. Store owners in downtown Curitiba threatened to file lawsuits against the local government but were quickly converted once they began to recognize a sharp increase in retail sales due to the pedestrian-friendly environment. Once downtown was under control, Lerner was able to develop the surrounding parks and public squares, refurbish historic buildings, and expand programs in support of local arts in order to make downtown Curitiba a central site of culture for the city (Figure 4). [9]

While protesters prevented cars from coming in, others destroyed the roadways behind them using pickaxes so the roads would be too damaged to drive on. Store owners in downtown Curitiba threatened to file lawsuits against the local government but were quickly converted once they began to recognize a sharp increase in retail sales due to the pedestrian-friendly environment. Once downtown was under control, Lerner was able to develop the surrounding parks and public squares, refurbish historic buildings, and expand programs in support of local arts in order to make downtown Curitiba a central site of culture for the city (Figure 4). [9]

The 2004 Master plan

After 40 years of transit and pedestrian oriented growth, Curitiba has seen a massive increase in the number of participants along bus and express lines. In its recently remodeled Master Plan from 2004, city planners hope to continue to develop their successful transit system. Their three guiding principles for the Master Plan (2004) are: 1) maintaining the guidelines established by the 1966 Master Plan; 2) consolidating important urban policies for the city; and 3) implementing new urban tools. Their last point focuses on the political aspect of planning in that planners are hoping to incorporate democratic management that “promotes public participation in the elaboration of complementary plans.” [10]

As Curitiba’s previous two plans have centered on transit oriented development, so will the 2004 Master Plan. The newest implementations from the 2004 plan include a greater focus on reducing carbon emissions and green house gasses by creating greater incentives and developing more attractive cycling infrastructure within the city’s core. Another way that planners hope to reduce emissions from the city’s heavily used bus system is to create a new Green Line that travels along the north-south axes. As this is one of the most often used routes for transitioning between lines, Curitiba hopes to reduce the amount of emissions produced by it. The 2004 Master Plan will have a significant impact on the infrastructure of the city by increasing the different modes of transportation available for citizens to use and will help to reduce the amount of strain put on the already impacted bus system (Figure 3). [10]

As Curitiba’s previous two plans have centered on transit oriented development, so will the 2004 Master Plan. The newest implementations from the 2004 plan include a greater focus on reducing carbon emissions and green house gasses by creating greater incentives and developing more attractive cycling infrastructure within the city’s core. Another way that planners hope to reduce emissions from the city’s heavily used bus system is to create a new Green Line that travels along the north-south axes. As this is one of the most often used routes for transitioning between lines, Curitiba hopes to reduce the amount of emissions produced by it. The 2004 Master Plan will have a significant impact on the infrastructure of the city by increasing the different modes of transportation available for citizens to use and will help to reduce the amount of strain put on the already impacted bus system (Figure 3). [10]

Future of Curitiba planning

Curitiba now has an exclusive tourist sightseeing bus to their BRT system. They are constantly running job training and business incubators for their citizens. In order to attract technology based businesses, they started building a technology park to get their economy a spot in that industry. It is currently one of the places in Brazil that has started putting money into alternative fuel technologies. [11]

It is a consensus among citizens of Curitiba that the leadership of the city should always stick to the city’s tradition of being at the forefront of sustainability and innovative infrastructure. These new leaders should be able to keep the cities traditions intact but yet be able to keep the city moving forward regarding technology that could help the city run efficiently. By keeping up with technologies, Curitiba can keep being the city that 41 cities have based their transportation system off of, along with the 46 more planning on being developed by using their advanced transportation network. [11]

It is a consensus among citizens of Curitiba that the leadership of the city should always stick to the city’s tradition of being at the forefront of sustainability and innovative infrastructure. These new leaders should be able to keep the cities traditions intact but yet be able to keep the city moving forward regarding technology that could help the city run efficiently. By keeping up with technologies, Curitiba can keep being the city that 41 cities have based their transportation system off of, along with the 46 more planning on being developed by using their advanced transportation network. [11]

Important people in curitiba planning

Figure 5. Jaime Lerner. Source: Fabio Campana

Figure 5. Jaime Lerner. Source: Fabio Campana

Jaime Lerner was the Mayor of Curitiba a few times and during his tenure he implemented many of the programs that Curitiba is known for such as the “Green Exchange” that made it possible to trade trash for something valuable like transit tokens or food (Figure 5). Lerner led the way with the innovative transit system in Curitiba. He completely changed public transit regarding not just the transport itself, but even the roads that carry the transit in order for the transit to run as efficiently and safely as possible. By making a successful public transportation system, he has made it so there are less cars, and when there are less cars, there are less accidents. There are only 4.2 traffic related deaths per 100,000 citizens while the average in the region is 9.6 traffic related deaths. Because of him and his forward thinking in planning, the city of Curitiba is one of the most coveted cities among planners. [12]

Domingos Henrique Bongestabs was a 1964 graduate from the Architecture and Urbanism Course of the School of Engineering at the Federal University of Paraná. He is the architect well known for some of the most famous buildings in Curitiba, including The Wire Opera House that was opened in 1992. To read more about Bongestabs and the Wire Opera House, please refer to the Green Spaces section of this website. [13]

Cassio Taniguchi was part of the group of people that helped Jaime Lerner implement the Curitiba Master Plan. He started working for Lerner in 1971. He is a civil engineer by trade. He eventually became the mayor of Curitiba from 1997 to 2005. When he was on Lerner’s team in the 1970s, he was the person that decided to make sure the city had an industrial center, that later became the center of the city’s manufacturing zone. During his tenure as mayor he was able to get some automotive companies to come to Curitiba and currently has the second largest auto industry in Brazil. One important project that Taniguchi had during his time as mayor was the Linhao de Emprezo. Linda de Emprezo taught unemployed citizens of Curitiba technical skills and then helped them start their own small businesses by leasing these citizens storefronts and offering tax reductions. [11]

Domingos Henrique Bongestabs was a 1964 graduate from the Architecture and Urbanism Course of the School of Engineering at the Federal University of Paraná. He is the architect well known for some of the most famous buildings in Curitiba, including The Wire Opera House that was opened in 1992. To read more about Bongestabs and the Wire Opera House, please refer to the Green Spaces section of this website. [13]

Cassio Taniguchi was part of the group of people that helped Jaime Lerner implement the Curitiba Master Plan. He started working for Lerner in 1971. He is a civil engineer by trade. He eventually became the mayor of Curitiba from 1997 to 2005. When he was on Lerner’s team in the 1970s, he was the person that decided to make sure the city had an industrial center, that later became the center of the city’s manufacturing zone. During his tenure as mayor he was able to get some automotive companies to come to Curitiba and currently has the second largest auto industry in Brazil. One important project that Taniguchi had during his time as mayor was the Linhao de Emprezo. Linda de Emprezo taught unemployed citizens of Curitiba technical skills and then helped them start their own small businesses by leasing these citizens storefronts and offering tax reductions. [11]

References

[1] History of Curitiba - Prefeitura de Curitiba. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.curitiba.pr.gov.br/idioma/ingles/historia

[2] History and Demographics. (1999, August 6). Curitiba Research and Urban Planning Institute. Retrieved February 23, 2015, from http://epat.wisc.edu/.energy/.metro/.format/.history.html

[3] Population. (n.d.) Retrieved February 10, 2015, from http://www.agencia.curitiba.pr.gov.br/

[4] Rabinovitch, J. (1996). A Success Story of Urban Planning: Curitiba. Scientific American). (Reprinted in Cities Built for People, U. Kirdar, 1997, New York: United Nations)

[5] Macedo, J. (2004). City Profile: Curitiba. Cities, 21(6), 537-549.

[6] History of Planning (n.d.) Retrieved March 2, 2015, from http://www.ippuc.org.br/default.php?idioma=5

[7] Macedo, J. (2013). Planning a Sustainable City: The Making of Curitiba, Brazil. Journal of Planning History, 12(4), 334-353.

[8] Higher Education in Regional and City Development. (2011). State of Parana, Brazil. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?isbn=9264089020

[9] Cervero, R. (1998). Creating a Linear City with a Surface Metro: Curitiba, Brazil. In The Transit Metropolis: A Global Inquiry (1st ed., pp. 265-293). Washington, D.C.: Island Press.

[10] Ababa, A. (2015, March 12). CODATU XV The Role of Urban Mobility In (Re)shaping Cities. Lecture presented at Curitiba: More than 40 Years of Urban Development and Transport Planning, Curitiba.

[11] Gnatek, T. (2003, December). Retrieved March, 2015, from http://www.pbs.org/ frontlineworld/fellows/brazil1203/

[12] Hidalgo, D. (2014, May 27). Urbanism Hall of Fame: Jaime Lerner – The architect of Curitiba. Retrieved February 24, 2015, from http://thecityfix.com/blog/urbanism- hall-fame-jaime-lerner-architect-curitiba-dario-hidalgo/

[13] Reconstituted History Architecture and Urbanism. (2001, June). Retrieved March, 2015, from http://au.pini.com.br/arquitetura-urbanismo/96/artigo23735-1.aspx

[2] History and Demographics. (1999, August 6). Curitiba Research and Urban Planning Institute. Retrieved February 23, 2015, from http://epat.wisc.edu/.energy/.metro/.format/.history.html

[3] Population. (n.d.) Retrieved February 10, 2015, from http://www.agencia.curitiba.pr.gov.br/

[4] Rabinovitch, J. (1996). A Success Story of Urban Planning: Curitiba. Scientific American). (Reprinted in Cities Built for People, U. Kirdar, 1997, New York: United Nations)

[5] Macedo, J. (2004). City Profile: Curitiba. Cities, 21(6), 537-549.

[6] History of Planning (n.d.) Retrieved March 2, 2015, from http://www.ippuc.org.br/default.php?idioma=5

[7] Macedo, J. (2013). Planning a Sustainable City: The Making of Curitiba, Brazil. Journal of Planning History, 12(4), 334-353.

[8] Higher Education in Regional and City Development. (2011). State of Parana, Brazil. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?isbn=9264089020

[9] Cervero, R. (1998). Creating a Linear City with a Surface Metro: Curitiba, Brazil. In The Transit Metropolis: A Global Inquiry (1st ed., pp. 265-293). Washington, D.C.: Island Press.

[10] Ababa, A. (2015, March 12). CODATU XV The Role of Urban Mobility In (Re)shaping Cities. Lecture presented at Curitiba: More than 40 Years of Urban Development and Transport Planning, Curitiba.

[11] Gnatek, T. (2003, December). Retrieved March, 2015, from http://www.pbs.org/ frontlineworld/fellows/brazil1203/

[12] Hidalgo, D. (2014, May 27). Urbanism Hall of Fame: Jaime Lerner – The architect of Curitiba. Retrieved February 24, 2015, from http://thecityfix.com/blog/urbanism- hall-fame-jaime-lerner-architect-curitiba-dario-hidalgo/

[13] Reconstituted History Architecture and Urbanism. (2001, June). Retrieved March, 2015, from http://au.pini.com.br/arquitetura-urbanismo/96/artigo23735-1.aspx