INTRODUCTION

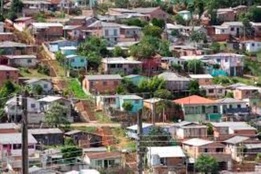

Figure 1. Curitiba Housing. Source: Viajar Pelomundo; Curitiba

Figure 1. Curitiba Housing. Source: Viajar Pelomundo; Curitiba

The stage: a city famous for its urban planning, emulated around the world. A city called “the envy of urban planners the world over” by travel website LonelyPlanet. Curitiba, Brazil. The situation: Brazil has been chosen to host the 2014 FIFA World Cup. Curitiba is to be one of the host cities. With the international spotlight being turned towards Curitiba, the city needs to prepare for the upcoming event. A situation arises. To build the best facilities for the World Cup, the city needs to build on land that has already been built upon. These locations include housing. Families are informed that their homes will be demolished, and that they need to leave. The city has nowhere for these families to go, and tells them that they will have to find new places to live in a city where housing is already scarce. So why does a city that is so greatly praised for its success, including in housing, have such a great failure in housing its residents? [1]

Housing is one of the most important parts of any city (Figure 1). In some ways, the housing of a city is what makes a city a city. Where housing and residential districts are situated in a city determines how residents of a city interact with their city. It determines how they get from place to place, and where they spend their leisure time. How the housing is designed creates a character for the city, and the character of individual neighborhoods within that city. The density of housing can have an effect on almost all aspects of a city, from the effectiveness of public transit, to how environmentally friendly the city is. Housing policy can be an important asset in fighting poverty, homelessness, and crime. Creating housing for a city is a monumental and incredibly difficult task to do effectively.

Curitiba is famous for its urban planning and its successes in comparison to other major cities in Brazil. The housing of Curitiba, an aspect of this progress, has met similar successes. It is, or was, in many ways, an excellent model of how to build housing for a growing city. Yet, at the same time, Curitiba still faces massive housing issues that seem unlikely to get any better in the near future. To add to this, Curitiba has made some decisions regarding housing that, while potentially advantageous for the city, attract criticism, and deservingly so. Housing in Curitiba is at once both one of the city’s greatest successes and greatest failures.

Housing is one of the most important parts of any city (Figure 1). In some ways, the housing of a city is what makes a city a city. Where housing and residential districts are situated in a city determines how residents of a city interact with their city. It determines how they get from place to place, and where they spend their leisure time. How the housing is designed creates a character for the city, and the character of individual neighborhoods within that city. The density of housing can have an effect on almost all aspects of a city, from the effectiveness of public transit, to how environmentally friendly the city is. Housing policy can be an important asset in fighting poverty, homelessness, and crime. Creating housing for a city is a monumental and incredibly difficult task to do effectively.

Curitiba is famous for its urban planning and its successes in comparison to other major cities in Brazil. The housing of Curitiba, an aspect of this progress, has met similar successes. It is, or was, in many ways, an excellent model of how to build housing for a growing city. Yet, at the same time, Curitiba still faces massive housing issues that seem unlikely to get any better in the near future. To add to this, Curitiba has made some decisions regarding housing that, while potentially advantageous for the city, attract criticism, and deservingly so. Housing in Curitiba is at once both one of the city’s greatest successes and greatest failures.

Successes

Figure 2. Density along axes. Source: Band News FM Curitiba

Figure 2. Density along axes. Source: Band News FM Curitiba

Curitiba's first, and most obvious, success in housing is simply having it, and having an organized city plan to go with it. In a city like Curitiba, this is an accomplishment. Curitiba was never a city with great wealth, and faced significant demographic changes in the 20th century. To have fared as well as it has in terms of providing housing to it’s residents is extremely impressive.

Curitiba’s housing history is not very remarkable before the middle of the twentieth century. The city was a relatively small state capital with a population of 180,000 in 1950. Then, in the 1950s, the city’s population began to grow at an extremely rapid pace, doubling between 1950 and 1960. In 2010, the city boasted a population of almost 1.8 million. This represents a massive, 1,000 percent population increase in 60 years. Very few cities ever experience a population growth of this size, yet Curitiba managed to handle the vast new population boom with relative grace and order. It is even rarer for cities to experience a massive population growth and be used as an example of effective urban planning. Despite these odds, Curitiba is an example of effective, sustainable development. [2]

Curitiba’s housing placement is largely based around the idea of “structural axes” that organize the city, put into place by the Wilhelm Plan. These were streets that radiated out from the center of the city. Density is highest around these axes, decreasing further away from the axes. This has led to a more orderly development, with impressively high densities. Housing densities along the axes are an average of 38 dwellings per acre. Closer to the center of the city, density is even higher (Figure 2). These axes and the housing density that they create represent a massive benefit to all things that density brings: more effective public transit, greater walkability, and greater sustainability. The city of Curitiba put a plan into place that created an organized and effective way to add housing. [3]

This plan can serve as an example to other cities around the world. The axes that Curitiba built had a massive effect on the density of housing in the areas surrounding the axes. Between the years of 1970 and 1992 as the city’s population boomed rapidly, these areas saw an incredible 855 percent increase in housing density. While, of course, every city’s situation is unique, the results of this plan combined with a rapidly growing population are undeniable. Not only that, the plan creates a natural pattern for public transit to follow, making public transit more efficient and more effective. Any city that is expecting a significant population growth in the near future can look to Curitiba to provide an example. [3]

The cities that can benefit the most, however, are rapidly growing cities in the developing world. Curitiba’s housing policies represent a potential pattern for sustainable, effective housing in developing cities. Developing cities are cities that are experiencing rapid population growth, with all the effects that go with that such as urbanization, industrialization, and the building of informal settlements. Developing cities can benefit from the increased density more than a city in a developing nation. Citizens of a developing nation will receive greater benefits from the increased access to public transit. Many require public transit to have access to jobs. In a developed nation, citizens are much more likely to be able to afford cars, even if there are substantial negatives to heavy car use. Developing cities also have the ability to set up a sustainable city in the future that avoids the extensive environmental issues many cities face, where as already developed cities require different types of sustainability efforts to make already existing infrastructure sustainable.

Curitiba’s housing history is not very remarkable before the middle of the twentieth century. The city was a relatively small state capital with a population of 180,000 in 1950. Then, in the 1950s, the city’s population began to grow at an extremely rapid pace, doubling between 1950 and 1960. In 2010, the city boasted a population of almost 1.8 million. This represents a massive, 1,000 percent population increase in 60 years. Very few cities ever experience a population growth of this size, yet Curitiba managed to handle the vast new population boom with relative grace and order. It is even rarer for cities to experience a massive population growth and be used as an example of effective urban planning. Despite these odds, Curitiba is an example of effective, sustainable development. [2]

Curitiba’s housing placement is largely based around the idea of “structural axes” that organize the city, put into place by the Wilhelm Plan. These were streets that radiated out from the center of the city. Density is highest around these axes, decreasing further away from the axes. This has led to a more orderly development, with impressively high densities. Housing densities along the axes are an average of 38 dwellings per acre. Closer to the center of the city, density is even higher (Figure 2). These axes and the housing density that they create represent a massive benefit to all things that density brings: more effective public transit, greater walkability, and greater sustainability. The city of Curitiba put a plan into place that created an organized and effective way to add housing. [3]

This plan can serve as an example to other cities around the world. The axes that Curitiba built had a massive effect on the density of housing in the areas surrounding the axes. Between the years of 1970 and 1992 as the city’s population boomed rapidly, these areas saw an incredible 855 percent increase in housing density. While, of course, every city’s situation is unique, the results of this plan combined with a rapidly growing population are undeniable. Not only that, the plan creates a natural pattern for public transit to follow, making public transit more efficient and more effective. Any city that is expecting a significant population growth in the near future can look to Curitiba to provide an example. [3]

The cities that can benefit the most, however, are rapidly growing cities in the developing world. Curitiba’s housing policies represent a potential pattern for sustainable, effective housing in developing cities. Developing cities are cities that are experiencing rapid population growth, with all the effects that go with that such as urbanization, industrialization, and the building of informal settlements. Developing cities can benefit from the increased density more than a city in a developing nation. Citizens of a developing nation will receive greater benefits from the increased access to public transit. Many require public transit to have access to jobs. In a developed nation, citizens are much more likely to be able to afford cars, even if there are substantial negatives to heavy car use. Developing cities also have the ability to set up a sustainable city in the future that avoids the extensive environmental issues many cities face, where as already developed cities require different types of sustainability efforts to make already existing infrastructure sustainable.

Failures

Figure 3. Favela in Curitiba. Source: Skyscraper City; Curitiba

Figure 3. Favela in Curitiba. Source: Skyscraper City; Curitiba

Curitiba has received vast praises for its successes. It has defied the expectations of the rest of Brazil as a result of its urban planning. Curitiba was called a “First World City” by the former mayor of Toronto, Arthur C. Eggleton, for its sophisticated urban planning and generally high standard of living. Yet, it does not manage to escape the issues that are so common in other Brazilian cities, such as poverty and unequal access to municipal services. [4]

The slums that are present in so many other cities in Brazil, the favelas, are still present throughout Curitiba (Figure 3). Urban poverty is still a massive issue that plagues Curitiba, and it is only getting worse as both population and housing prices increase. Because of the demand for housing, the cost of living in the city, so famous for its urban planning in the past several decades, hasn’t implemented anything significant for aiding the urban poor recently. The city, instead, has largely relied on its reputation in recent years for keeping up its image. [4] [5]

It is estimated that 10 to 15 percent of the city of Curitiba’s population lives in substandard housing that does not meet an acceptable level of health and safety standards. Not only that, both the number of people living in favelas, and the number of favelas themselves are increasing. These favelas are not planned, officially approved, or regulated, but built on what land is available by the poor to live on. For a city that has the label of “First World City,” this is a massive portion of the population living in informal settlements. [4]

A significant portion of the population growth in the city comes from people moving from other Brazilian cities. As more people arrive in the city, the housing shortage becomes worse and more people are forced to live in favelas. Favelas in Curitiba are not any better than favelas in other Brazilian cities, and the recent migrants to the city face the risk of living in these favelas. [4]

The favelas in Curitiba, like slums in every city, have very low standards of living, usually missing basic services. The most pressing issues in Curitiba’s favelas are the lack of sanitation services. Most of the city has access to a waste disposal system of some sort, with 77% of households having access to the city’s sewage system, and a further 15.5% of households having access to a septic tank. The remainder of the city’s households, 7.5%, have no waste disposal system. These households are some of the city's poorest, and located in the favelas. The lack of sanitation system results in waste being dumped into storm drains or open ditches. This lack of access to a sanitation system is a major public health issue for Curitiba. [4]

Curitiba does have a housing assistance program to, in theory, help reduce the number of favelas and the amount of people living in them. Yet most of the housing assistance programs are focused on families that earn at least the equivalent of three or more minimum wages a month. That’s at a minimum, and most housing assistance programs require higher wages. These programs leave the city’s poorest residents unaided. [4]

The slums that are present in so many other cities in Brazil, the favelas, are still present throughout Curitiba (Figure 3). Urban poverty is still a massive issue that plagues Curitiba, and it is only getting worse as both population and housing prices increase. Because of the demand for housing, the cost of living in the city, so famous for its urban planning in the past several decades, hasn’t implemented anything significant for aiding the urban poor recently. The city, instead, has largely relied on its reputation in recent years for keeping up its image. [4] [5]

It is estimated that 10 to 15 percent of the city of Curitiba’s population lives in substandard housing that does not meet an acceptable level of health and safety standards. Not only that, both the number of people living in favelas, and the number of favelas themselves are increasing. These favelas are not planned, officially approved, or regulated, but built on what land is available by the poor to live on. For a city that has the label of “First World City,” this is a massive portion of the population living in informal settlements. [4]

A significant portion of the population growth in the city comes from people moving from other Brazilian cities. As more people arrive in the city, the housing shortage becomes worse and more people are forced to live in favelas. Favelas in Curitiba are not any better than favelas in other Brazilian cities, and the recent migrants to the city face the risk of living in these favelas. [4]

The favelas in Curitiba, like slums in every city, have very low standards of living, usually missing basic services. The most pressing issues in Curitiba’s favelas are the lack of sanitation services. Most of the city has access to a waste disposal system of some sort, with 77% of households having access to the city’s sewage system, and a further 15.5% of households having access to a septic tank. The remainder of the city’s households, 7.5%, have no waste disposal system. These households are some of the city's poorest, and located in the favelas. The lack of sanitation system results in waste being dumped into storm drains or open ditches. This lack of access to a sanitation system is a major public health issue for Curitiba. [4]

Curitiba does have a housing assistance program to, in theory, help reduce the number of favelas and the amount of people living in them. Yet most of the housing assistance programs are focused on families that earn at least the equivalent of three or more minimum wages a month. That’s at a minimum, and most housing assistance programs require higher wages. These programs leave the city’s poorest residents unaided. [4]

Figure 4. A Cohab-CT Project. Source: Fabio Campana; Curitiba

Figure 4. A Cohab-CT Project. Source: Fabio Campana; Curitiba

Approximately 37% of Curitiba’s population does not earn the required equivalent to three minimum wages per month. These residents are aided by a program called Cohab-CT, Curitiba’s low-income housing authority (Figure 4). Cohab-CT is linked to a federal government program, the Housing Financing System, that provides funding for affordable housing projects throughout Brazil. Residents can register with Cohab-CT to receive financial assistance in renting or purchasing a home from the program. Approximately 70% of those registered earn the equivalent of between one and three minimum wages a month. This program has had some successes, but there are still tens of thousands of families that are registered with Cohab-CT that have not been provided adequate housing. [4]

Successes from Failure

Curitiba has a lot of potential for improvements in many areas of its housing policy. Yet, Curitiba has been creative in how it approaches these issues, not letting the large issues get in the way of other successes. Curitiba implements programs that have to do with the favelas that focus on improving life there or improving the success of the city as a whole. The city recognizes that it hasn’t been as successful as it could be in the area of urban poverty, but institutes smaller programs that don’t have the extremely large resource requirement that fighting urban poverty does.

One such program is a public works program that focuses on increasing citizens’ access to running water. As a result of this program, 98.6% of households in Curitiba are connected to the public water system. The benefits of this program are twofold: not only is it a public works program that puts people to work, it also provides running water to almost the entire city. Even most of those living in favelas have access to running water, an incredible achievement. Curitiba recognized that the fight to end favelas and provide adequate housing for all is one that is unlikely to end anytime soon, and created a quality of life improvement for those living within these favelas. [4]

Another successful example is the green exchange program, which allows residents of the favelas to exchange garbage they bring out of the favelas for food, creating garbage removal in an area of the city inaccessible to municipal garbage collection. For more information on this program, see the Environmental Management section under Urban Design.

One such program is a public works program that focuses on increasing citizens’ access to running water. As a result of this program, 98.6% of households in Curitiba are connected to the public water system. The benefits of this program are twofold: not only is it a public works program that puts people to work, it also provides running water to almost the entire city. Even most of those living in favelas have access to running water, an incredible achievement. Curitiba recognized that the fight to end favelas and provide adequate housing for all is one that is unlikely to end anytime soon, and created a quality of life improvement for those living within these favelas. [4]

Another successful example is the green exchange program, which allows residents of the favelas to exchange garbage they bring out of the favelas for food, creating garbage removal in an area of the city inaccessible to municipal garbage collection. For more information on this program, see the Environmental Management section under Urban Design.

The dark side of housing

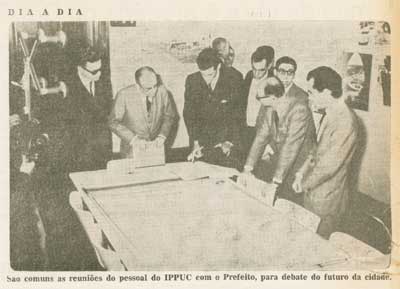

Figure 5. IPPUC. Source: IPPUC

Figure 5. IPPUC. Source: IPPUC

Curitiba’s housing policy, although perhaps not deserving of the amount of praise it has received, still, on the surface level, seems to have a very positive policy. Where there are failures, they come from larger issues. Curitiba isn’t intentionally doing anything wrong, it just hasn’t been able to do enough to solve the issues. Indeed, the city is making progress in some of these areas. In that view, it makes sense to praise the housing policy of Curitiba. The city isn’t doing anything wrong, right? Not exactly.

Curitiba’s planning agency, the Instituto de Pesquisae Planejamento Urbano de Curitiba, or IPPUC, (Figure 5) is an extremely powerful entity within the city. The agency’s power is one of the reasons Curitiba could have such effective urban planning, because the agency could largely do what it wanted despite opposition. This power has been used for less than savory purposes as well, however. An example of this misuse of power involves Curitiba’s plan to be one of the host cities for the FIFA World Cup in 2014. The IPPUC put forward a plan that included a change of priorities for the cities. More worrisome, the IPPUC proposed as part of this plan to remove residents from the sites of the planned new structures. The IPPUC did not provide an sort of resettlement plan for those displaced. [5]

A plan such as this one merits some serious criticisms of Curitiba. The city desired so greatly to be seen on the world stage that the planning agency was willing to remove residents from the city. The city and the IPPUC could have created a resettlement plan for these residents. It would have cost time and money, but it could have been done. The IPPUC didn’t, however, because there wasn’t a limit or regulation on its power in this area. The agency could propose such a plan and not have to worry about any sort of opposition or punishment.

Curitiba’s planning agency, the Instituto de Pesquisae Planejamento Urbano de Curitiba, or IPPUC, (Figure 5) is an extremely powerful entity within the city. The agency’s power is one of the reasons Curitiba could have such effective urban planning, because the agency could largely do what it wanted despite opposition. This power has been used for less than savory purposes as well, however. An example of this misuse of power involves Curitiba’s plan to be one of the host cities for the FIFA World Cup in 2014. The IPPUC put forward a plan that included a change of priorities for the cities. More worrisome, the IPPUC proposed as part of this plan to remove residents from the sites of the planned new structures. The IPPUC did not provide an sort of resettlement plan for those displaced. [5]

A plan such as this one merits some serious criticisms of Curitiba. The city desired so greatly to be seen on the world stage that the planning agency was willing to remove residents from the city. The city and the IPPUC could have created a resettlement plan for these residents. It would have cost time and money, but it could have been done. The IPPUC didn’t, however, because there wasn’t a limit or regulation on its power in this area. The agency could propose such a plan and not have to worry about any sort of opposition or punishment.

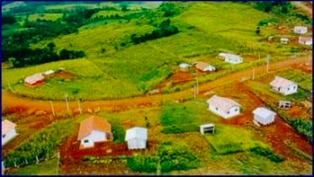

Figure 6. Projeto Vilas Rurais. Source: Cidades do Brasil

Figure 6. Projeto Vilas Rurais. Source: Cidades do Brasil

Curitiba’s plan for to be one of the host cities of the 2014 FIFA World Cup was actually somewhat unusual when it comes to the less savory side of Curitiba’s housing policy. Usually, Curitiba seems to try to portray itself as a model city that does thing differently from other Brazilian cities. In reality, Curitiba just tends to push the worst parts of the typical Brazilian city to outside the city limits. This way, Curitiba’s statistics look good, and as long as a person doesn’t leave the city, the city appears to be like the sustainable city that Curitiba is frequently billed as.

An example of this is the favelas of Curitiba. Although Curitiba itself has fewer favelas than other Brazilian cities, this isn’t the case for the region immediately surrounding Curitiba. Favelas have largely just been pushed from within the city limits to just outside of them. This means that certain statistics, such as the urban poverty rate, don’t show the whole picture. The statistics given earlier about favelas are limited to those within the city limits. In reality, the figures are likely much higher, although these numbers are more difficult to quantify. These favelas also lack the benefits of many of the city programs that Curitiba has been praised for. [2]

Another program that Curitiba has put into place to ostensibly reduce the housing crisis is the Projeto Vilas Rurais, or Rural Village Program, instituted in 1994 (Figure 6). The program is relatively simple: because of the cost of housing in Curitiba, the city built rural villages outside the city limits to house rural immigrants. The goal of these villages was to provide housing, and a small plot of land, to new immigrants to the city that would otherwise end up living in the favelas. The project targeted landless peasants who had very little wealth. In connection with this program, another program was begun that provided free bus tickets for the villagers to return from the city to the village. The aim was to house 50,000 people in these villages. The landless workers, however, did not see these villages as a beneficial program. The Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra, or Landless Workers movement, claimed that the programs goals were to reduce dissent within the city. [3]

The logic behind this claim makes sense. By placing these rural workers far away from the city, Curitiba reduced the amount of migration to the city. This, in turn, reduced the strain on the city’s various housing programs. More importantly, the program kept the poor out of favelas. This way, the favelas, the most difficult area of the city to control and keep safe, would not grow. This came at the expense of the rural workers who ended up living in the villages. They did not have access to what the city could potentially offer them. All these rural workers received was a small plot of land.

These negative actions are not to say that Curitiba isn’t an example of sustainable development in the realm of housing. It absolutely is, but Curitiba should also not be taken as a city that can do no wrong. The city has been hugely successful, especially in relation to other Brazilian cities. One of the reasons for this level of success are these less savory actions. The IPPUC is so effective because it has powers, and the Projeto Vilas Rurais did help reduce population inflow to the city, which aided sustainable development. Ultimately, it should be recognized that while the city is better off overall, there have been losers in the housing policy of Curitiba.

An example of this is the favelas of Curitiba. Although Curitiba itself has fewer favelas than other Brazilian cities, this isn’t the case for the region immediately surrounding Curitiba. Favelas have largely just been pushed from within the city limits to just outside of them. This means that certain statistics, such as the urban poverty rate, don’t show the whole picture. The statistics given earlier about favelas are limited to those within the city limits. In reality, the figures are likely much higher, although these numbers are more difficult to quantify. These favelas also lack the benefits of many of the city programs that Curitiba has been praised for. [2]

Another program that Curitiba has put into place to ostensibly reduce the housing crisis is the Projeto Vilas Rurais, or Rural Village Program, instituted in 1994 (Figure 6). The program is relatively simple: because of the cost of housing in Curitiba, the city built rural villages outside the city limits to house rural immigrants. The goal of these villages was to provide housing, and a small plot of land, to new immigrants to the city that would otherwise end up living in the favelas. The project targeted landless peasants who had very little wealth. In connection with this program, another program was begun that provided free bus tickets for the villagers to return from the city to the village. The aim was to house 50,000 people in these villages. The landless workers, however, did not see these villages as a beneficial program. The Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra, or Landless Workers movement, claimed that the programs goals were to reduce dissent within the city. [3]

The logic behind this claim makes sense. By placing these rural workers far away from the city, Curitiba reduced the amount of migration to the city. This, in turn, reduced the strain on the city’s various housing programs. More importantly, the program kept the poor out of favelas. This way, the favelas, the most difficult area of the city to control and keep safe, would not grow. This came at the expense of the rural workers who ended up living in the villages. They did not have access to what the city could potentially offer them. All these rural workers received was a small plot of land.

These negative actions are not to say that Curitiba isn’t an example of sustainable development in the realm of housing. It absolutely is, but Curitiba should also not be taken as a city that can do no wrong. The city has been hugely successful, especially in relation to other Brazilian cities. One of the reasons for this level of success are these less savory actions. The IPPUC is so effective because it has powers, and the Projeto Vilas Rurais did help reduce population inflow to the city, which aided sustainable development. Ultimately, it should be recognized that while the city is better off overall, there have been losers in the housing policy of Curitiba.

REFERENCES

[1] Introducing Curitiba. LonelyPlanet.

[2] Macedo, J. (2013). Planning a Sustainable City: The Making of Curitiba Brazil, Journal of Planning History 12(4).

[3] Moore, S. A. (2006). Alternative Routes to the Sustainable City: Austin, Curitiba, and Frankfurt. Lanham: Lexington Books.

[4] Macedo, J. (2004). City Profiles: Curitiba. Cities 21(6).

[5] Halais, F. (2012). Has South America’s Most Sustainable City Lost its Edge?. CityLab.

[2] Macedo, J. (2013). Planning a Sustainable City: The Making of Curitiba Brazil, Journal of Planning History 12(4).

[3] Moore, S. A. (2006). Alternative Routes to the Sustainable City: Austin, Curitiba, and Frankfurt. Lanham: Lexington Books.

[4] Macedo, J. (2004). City Profiles: Curitiba. Cities 21(6).

[5] Halais, F. (2012). Has South America’s Most Sustainable City Lost its Edge?. CityLab.