INTRODUCTION

Figure 1. Curitiba axes. Source: Nani The Star; Curitiba

Figure 1. Curitiba axes. Source: Nani The Star; Curitiba

In 1943, the Agache Plan was made by a French urbanist by the name of Alfred Agache. Since Curitiba started growing more rapidly than anticipated, first zoning acts were passed in 1953 while the first mass transit was planned in 1955. By the 1960s, the Agache Plan was barely in use and already required changes. In 1965, there was a competition for someone to make the new master plan. Planner-Architect Jorge Wilheim’s firm won the competition and the main thing that was different about his plans compared to Agache was having “radiating axes” from the center of Curitiba (Figure 1), he inserted public transit and had “mixed land-use” principles. Mixed land-use meaning housing integrated into the transit corridors. The axes left the center of the city, as if to force growth in those particular directions because that is where the transit would be placed. As you get further from these main axes roads, the housing gets less dense. The plan was ultimately approved in 1966. [1] [2]

Along with the axes, zones were made in order for different types of structures to be built. Among the zones, residential zones were put by public transit and there were certain areas that were similar to historic districts established in order to get restoration done on important historical buildings. They are called “special preservation units” and when those units are sold all earned money is only used on saving buildings. There is also the Central Zone and Structural Sectors for commercial areas. There are actually 50 specific zone types in Curitiba as of the year 2000. One area that was not part of the Wilheim plan to get developers interested in developing was in the southwest part of the city. This might not seem controversial, but the fact that it had preferred topography and was not located by any of the water supply watersheds meant the new residents were more than likely affluent. The southwest part of the city became the priority while the rest of the city, especially the poorer southeast area with squatted homes became subject to environmental injustices. [1] [2] [3]

Along with the axes, zones were made in order for different types of structures to be built. Among the zones, residential zones were put by public transit and there were certain areas that were similar to historic districts established in order to get restoration done on important historical buildings. They are called “special preservation units” and when those units are sold all earned money is only used on saving buildings. There is also the Central Zone and Structural Sectors for commercial areas. There are actually 50 specific zone types in Curitiba as of the year 2000. One area that was not part of the Wilheim plan to get developers interested in developing was in the southwest part of the city. This might not seem controversial, but the fact that it had preferred topography and was not located by any of the water supply watersheds meant the new residents were more than likely affluent. The southwest part of the city became the priority while the rest of the city, especially the poorer southeast area with squatted homes became subject to environmental injustices. [1] [2] [3]

GREEN SPACES

A kind of spontaneous use of the land was observed in the 1970s in Curitiba along the Barigui river, in the Southwest of the city, beyond the industrial zone. This illegal parcelling and recreational use of the land, however dangerous for the environment shows the demand for green space in Curitiba. Considering that a cultural life in the city comes from the presence of its inhabitants, this initiative is actually the first actual proof for a cultural revitalization. It has been followed by many other initiative such as creating places where the people can actually meet and enjoy the city in public spaces without any goal but the enjoyment itself. This is where comes the second step of this process: the integration of more green spaces. To realize the importance of this point and the depth of the change, we have have to bear in mind two figures relating to the green spaces in Curitiba. In 20 years, Curitiba went from 0.5 meter square of green space per person to 50 meters square per person. At this level, we can legitimately talk of disruption in the way people live in the city. This increase has been given possible thanks to the use of former industrial areas and quarries. The other effect of this rehabilitation of unused or misused space is that it helps preserve the rivers, and the nature in Curitiba. Serving the people also led to protecting nature. This great transformation should not be seen as the last step. [4]

the use of green spaces

Figure 2. UNILIVRE architecture merges with its surrounding nature. Source: Apolar

Figure 2. UNILIVRE architecture merges with its surrounding nature. Source: Apolar

The green space creation is the step that allowed a great cultural revitalization. Just think about the fact that people of Curitiba were able to stroll in their city, hang out in green spaces, it literally brings life in the city. The step that actually finds a use in those green spaces is revitalizing the cultural life with an institution. The best example of this revitalization through and in those green spaces is the UNILIVRE (Independent University of Environment). It is located in the north-east of the City. The building was designed by Domingos Henrique Bongestabs and his idea was to completely merge the building and its surrounding nature (Figure 2). The building is wooden and literally mixes with the nature around, it’s almost hidden in the trees of the park. The idea is that the University really proves what it stands for: sustainability is possible. The classrooms are surrounded by a luxuriant nature, the only path to access the entrance leads to an artificial lake with black swans.

The artificial lake in the new park plays a major role in flood control, they are not only aesthetic elements. This initiative really shows how much a city can merge with its nature and this idea can be turned to reality. This building is the key element that embodies this ability in Curitiba to make the city more friendly toward its pedestrians, showing that building doesn’t come in opposition to nature and that green spaces should not be associated with emptiness. Obviously, this example is a pinnacle and can’t be reproduced everywhere but it shows that an alternative way is possible, we really have to bear in mind that this building is a sort of showcase. This showcase mission is really highlighted by the fact that they display within each of those parks information about sustainability and ecology. [5]

The artificial lake in the new park plays a major role in flood control, they are not only aesthetic elements. This initiative really shows how much a city can merge with its nature and this idea can be turned to reality. This building is the key element that embodies this ability in Curitiba to make the city more friendly toward its pedestrians, showing that building doesn’t come in opposition to nature and that green spaces should not be associated with emptiness. Obviously, this example is a pinnacle and can’t be reproduced everywhere but it shows that an alternative way is possible, we really have to bear in mind that this building is a sort of showcase. This showcase mission is really highlighted by the fact that they display within each of those parks information about sustainability and ecology. [5]

Figure 3. Opera de Arame: the entrance is over the artificial lake. Source: Ferias pelo Brasil

Figure 3. Opera de Arame: the entrance is over the artificial lake. Source: Ferias pelo Brasil

We can find another of this trend and this idea that consists in showing how a green space can be used. The initiative comes from the same architect Domingos Henrique Bongestabs. It’s the Opera de Arame in Curitiba (Figure 3). It’s located 1 mile north from the UNILIVRE, in the Parque Pedreira Paulo Leminski. It follows the same design idea that a building can merge in the nature as in the UNILIVRE but it explores another side and in the case of the opera, it’s about reusing lands. The peculiarity of this building is that it has been settled in a reused granite quarry. It’s made of tubes of steel and glass. The view from inside the Opera is once again only the lush forest, the same as the classrooms. With the Opera, we go beyond the simple showcase, we can see that it’s a real policy that structures the whole city. [6]

Environmental Management

Figure 4. Example of a river overflow park. Source: Best Day; Curitiba

Figure 4. Example of a river overflow park. Source: Best Day; Curitiba

With the Iguazu River originating in Curitiba and due to the large population growth of Curitiba within the latter part of the 20th century, there have been some unforeseen environmental issues to deal with. One of the issues was Curitiba’s built environment growing into areas where they can easily be flooded by the river (Figure 4).

After trying to canal the various parts of the river system by canaling both underground and in the open, the city realized that they were not really solving the problem of flooding, but just moving the water around the city. As a matter of fact, after dredging parts of the river, the depth only changed by 40cm. It was decided by a group of planners that something else needed to be done to handle the flooding issue. By working around a federal funding problem that said flood control money can only be used for infrastructure for containing flood waters, they used that money to take care of the areas beside the river by making them “protected wooded areas” and no longer permitted any type of building. [7]

By the 1970s, Curitiba had 2 parks that sat beside rivers that totaled 2,000,000 square meters of open space. In 1982, Curitiba had opened their largest river park, Iguazu Park, which had 8,000,000 square meters. After Iguazu Park was established, Passauna Park was made to protect the Passauna River from contamination and it is 43,000,000 square meters of wooded space. [7]

By making parks be a way to help with rising river levels, it ultimately helped make the city much more green than they ever even planned. Another unforeseen environmental issue the land conservation helped with was keeping shantytown type areas from popping up in the middle of the city. In a way, by protecting the land from overflowing rivers, they inadvertently shaped the city into a cornerstone city in modern urban planning practices.

Another big environmental issue Curitiba has dealt with is garbage and recycling problems. Since citizens were not understanding the long-term effects of not recycling and taking care of trash correctly, meetings between residents and citizens occurred for environmental education programs. These environmental education programs led to a required environmentalism course in all public schools in the city. When Mayor Roberto Requiao was elected in the 1980s, he decided to start a department called the Municipal Department of Environmental Protection. The main objective of the department was to start making public policy regarding waste management, green area preservation, arborization, and reducing degradation of the urban space in the city. [7]

By the late 1980s, due to budget cuts, the number of garbage trucks on the road had to be lowered. Due to the lower amount of trucks, Curitiba decided to make a program in order for people to keep wanting to sort waste correctly. The first Curitiba waste program was called the “Garbage Purchase”. The “Garbage Purchase” program was where people collected their own trash, disposed of it in bins, and then received a bus ticket for each filled bag they turn in. The Garbage Purchase eventually became the “Green Exchange” program where citizens can recycle waste for vegetables. [7]

After trying to canal the various parts of the river system by canaling both underground and in the open, the city realized that they were not really solving the problem of flooding, but just moving the water around the city. As a matter of fact, after dredging parts of the river, the depth only changed by 40cm. It was decided by a group of planners that something else needed to be done to handle the flooding issue. By working around a federal funding problem that said flood control money can only be used for infrastructure for containing flood waters, they used that money to take care of the areas beside the river by making them “protected wooded areas” and no longer permitted any type of building. [7]

By the 1970s, Curitiba had 2 parks that sat beside rivers that totaled 2,000,000 square meters of open space. In 1982, Curitiba had opened their largest river park, Iguazu Park, which had 8,000,000 square meters. After Iguazu Park was established, Passauna Park was made to protect the Passauna River from contamination and it is 43,000,000 square meters of wooded space. [7]

By making parks be a way to help with rising river levels, it ultimately helped make the city much more green than they ever even planned. Another unforeseen environmental issue the land conservation helped with was keeping shantytown type areas from popping up in the middle of the city. In a way, by protecting the land from overflowing rivers, they inadvertently shaped the city into a cornerstone city in modern urban planning practices.

Another big environmental issue Curitiba has dealt with is garbage and recycling problems. Since citizens were not understanding the long-term effects of not recycling and taking care of trash correctly, meetings between residents and citizens occurred for environmental education programs. These environmental education programs led to a required environmentalism course in all public schools in the city. When Mayor Roberto Requiao was elected in the 1980s, he decided to start a department called the Municipal Department of Environmental Protection. The main objective of the department was to start making public policy regarding waste management, green area preservation, arborization, and reducing degradation of the urban space in the city. [7]

By the late 1980s, due to budget cuts, the number of garbage trucks on the road had to be lowered. Due to the lower amount of trucks, Curitiba decided to make a program in order for people to keep wanting to sort waste correctly. The first Curitiba waste program was called the “Garbage Purchase”. The “Garbage Purchase” program was where people collected their own trash, disposed of it in bins, and then received a bus ticket for each filled bag they turn in. The Garbage Purchase eventually became the “Green Exchange” program where citizens can recycle waste for vegetables. [7]

Green Exchange: Cambio Verde

“We no longer have rats, cockroaches, or the smell of rotting garbage.”

Poverty rates and income levels in Curitiba are typical of the surrounding area, but because of the planning efforts within the city, the city enjoys lower levels of pollution, a lower crime rate, and the education levels are higher. In response to the high levels of people in poverty living in favelas, the city has used creative means to try and help. One program implemented is called the 'green exchange', or ‘cambio verde’, employment program. Social inclusion is the focus of the program. People living in the favelas are encouraged to bring their bags of trash to collection centers, because the trash trucks are unable to reach most areas of the favelas. “We no longer have rats, cockroaches, or the smell of rotting garbage,” said a 25 year old mother of 2 living in the favelas, as she was waiting to exchange garbage receipts for eggs. At these trash collections centers, the bags full of trash can be traded for bus tickets and food. Four pounds of recyclables can be traded for one pound of fruit, vegetables, and eggs. Exchanging plastic bags and two liters of used oil also yields one pound of fresh food. There are about 10,000 people who participate in the program, who otherwise would not have any way to earn a living. Some people have 6 by 4 foot, two wheeled carts that can be piled up to 12 feet high with cardboard for recycling. The benefits of this program are multifaceted. The people from favelas get much needed nourishment, there is less litter around the city, and garbage is kept out of rivers and other sensitive areas. There is a similar program where low income children can earn school supplies, toys, candy, or show tickets for turning in trash that is recyclable. An expected bonus of the green exchange program is that after the program was up and running for awhile, it was noticed that the incidence of a particular disease that is mosquito borne was nearly completely eliminated. [2] [8] [9] [10]

Poverty rates and income levels in Curitiba are typical of the surrounding area, but because of the planning efforts within the city, the city enjoys lower levels of pollution, a lower crime rate, and the education levels are higher. In response to the high levels of people in poverty living in favelas, the city has used creative means to try and help. One program implemented is called the 'green exchange', or ‘cambio verde’, employment program. Social inclusion is the focus of the program. People living in the favelas are encouraged to bring their bags of trash to collection centers, because the trash trucks are unable to reach most areas of the favelas. “We no longer have rats, cockroaches, or the smell of rotting garbage,” said a 25 year old mother of 2 living in the favelas, as she was waiting to exchange garbage receipts for eggs. At these trash collections centers, the bags full of trash can be traded for bus tickets and food. Four pounds of recyclables can be traded for one pound of fruit, vegetables, and eggs. Exchanging plastic bags and two liters of used oil also yields one pound of fresh food. There are about 10,000 people who participate in the program, who otherwise would not have any way to earn a living. Some people have 6 by 4 foot, two wheeled carts that can be piled up to 12 feet high with cardboard for recycling. The benefits of this program are multifaceted. The people from favelas get much needed nourishment, there is less litter around the city, and garbage is kept out of rivers and other sensitive areas. There is a similar program where low income children can earn school supplies, toys, candy, or show tickets for turning in trash that is recyclable. An expected bonus of the green exchange program is that after the program was up and running for awhile, it was noticed that the incidence of a particular disease that is mosquito borne was nearly completely eliminated. [2] [8] [9] [10]

Garbage that's not garbage

Around 70% of Curitiba's trash is recycled by the residents, and 100% of households recycle. The program is called “garbage that's not garbage”, and the money raised from recycling is used for social programs and health services to help the poor. Having the residents sort the recyclables before they get collected saves the city the cost of having to plan for and run an extra recycling sorting facility. There is a garbage separation plant that employs homeless people to do the separating of refuse items that are not recyclable. An assistant to Jaime Lerner, named Nicolai Kluppel, came up with idea of a mechanized sorting system to sort recyclables, and was given the 'ok' to start the program. Jaime Lerner told him to 'go do it but there is no budget for it.' Kluppel was able to reuse discarded factory machinery to set up an assembly line type system for workers to sort everything that is recyclable from the trash. 'All Clean' is a program that hires either retired or unemployed people temporarily, to assist in trash pickup around the city, wherever it may be needed at the time. The planning of these programs helps conserve the resources of the city, helps with city beautification, and also provides employment to people who may not otherwise be able to find work. [2] [8] [10] [11]

Policies and Education

Figure 5. Recycling Bins. Source: Webpage Development; Curitiba Case Study

Figure 5. Recycling Bins. Source: Webpage Development; Curitiba Case Study

Curitiba has progressive policies dealing with waste and recycling (Figure 5). Strict environmental standards in the city keep all hazardous waste, as well as construction and demolition debris out of the lone landfill. Since 1989, Curitiba has taught its schoolchildren about environmentalism and sustainability. They teach conservation, recycling, and a range of other issues regarding the environment. At Christmas time, the children are given gifts of toys made from recycled plastic after having brought in plastic to be recycled during the school year. There are 9 bus terminals scattered around the city that serve as trash collection sites, which assists in keeping the number of garbage collection trucks low. Fast food type restaurants utilize real plates and real silverware, instead of disposable type containers. The integration of these programs into the planning of the city has kept Curitiba's image polished as a sustainable and forward thinking city. [12]

Contradictions in Curitiba

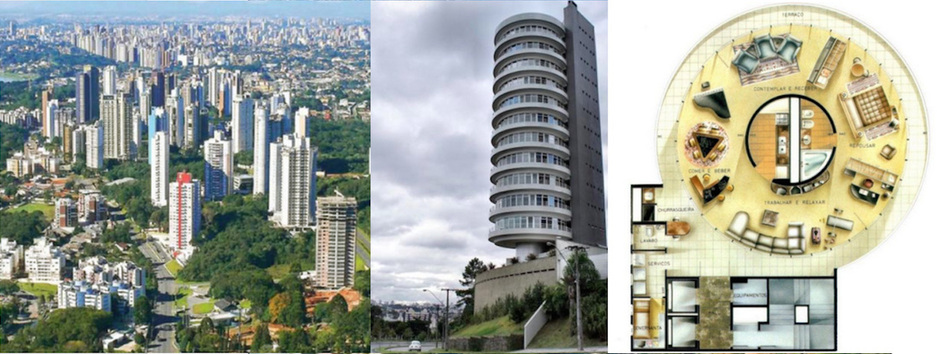

Figure 6. Ecoville (left) and the Suite Vollard (middle and right). Sources: www.io9.com - Chavesnamao

Figure 6. Ecoville (left) and the Suite Vollard (middle and right). Sources: www.io9.com - Chavesnamao

When a person thinks of Curitiba, they might think of community and openness, but within recent years there has been a want to get away from the city and to be able to have the city at arm’s length. Ecoville is very similar to a gated suburb (Figure 6). These gated complexes in Curitiba that have a design reminiscent of a “city in the park” look with plenty of use of defensible space details to keep others out of their complexes.

The Ecoville area of Curitiba consists of a group of high-rises with apartments. One particular building, Suite Vollard, is an 11 story building and each floor is one home (Figure 6). This is not an average apartment building though because each floor rotates. The people that live in these buildings in Ecoville consider living in the heart of the city as undesirable. While all these extravagant buildings are being built in Ecoville, some of which even sit empty, there are thousands of people on waiting lists for the public housing offered in Curitiba. [13]

While Ecoville is an example of a closed off community Curitiba, there are also places like Alphaville. Alphaville is considered an edge city that is a hybrid between Ecoville and Curitiba. Alphaville is a community that has gotten too big for its walls, so they keep their gated communities, but they open themselves up to nearby businesses and other public areas. For example, in the community of Alphaville called Graciosa, there is a freeway where Graciosa residents can directly access Curitiba and also access a close by coastal mountain range. In order to access Graciosa, almost 3 million dollars had to be spent for road infrastructure. It was unfortunately not for public transit, but roads for automobiles. Both of these case studies can make a person wonder if no city is immune to typical sprawl issues since it does not even work in Curitiba. [13] [14]

There are some landmarks representing different ethnic groups. It is as if Curitiba is some how trying to make it seem like they have deep seated traditional European roots. By doing this, they also failed to leave out the bad parts of their past. They are seemingly trying to “edit history” via their park designs. It has even been compared to Epcot Center because of how hard they try to work their supposed diversity into the local architecture. To make matters worse, the monument choices are heavily scrutinized by local government and the elite as to cater to rich residents of Curitiba who the government and elite believe are potential investors of the city. [10]

Starting in 1950, Curitiba’s population doubled every 10 years for 30 years, the idea was that if they dealt with the possible population increase by dealing with the built environment it would control the cultural issues. Anyone with any common sense knows that did not work. By having a nice built environment, the hope was not to necessarily get the approval of the Curitiba citizens, but the rest of the world. By doing this, they became this novel “model city” to the rest of the world. They became this contemporary version of a mystical fairytale type city with revolutionary planning. By spending so much time trying to appeal to the rest of the world, they left their citizens behind and their quality of life has dropped drastically. Curitiba now has to deal with issues that other large cities have to deal with like traffic problems, violence, and unemployment. [2]

REFERENCES

[1 ]Del Rio, V. (2009). Contemporary urbanism in Brazil: Beyond Brasília. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

[2] Macedo, J. (2004). Curitiba. Cities. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2004.08.008

[3] Suzuki, H. (2010). Eco2 cities: Ecological cities as economic cities. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

[4] Montaner, J. (1999). el modelo Curitiba: movilidad y espacios verdes, Ecología Política, 17

[5] Rabinovitch, J. (1992). Curitiba: towards sustainable urban development, Environment and urbanization, 4(2)

[6] Macedo, J. (2013). Planning a Sustainable City: The Making of Curitiba, Brazil. Journal of Planning History, 12(4), 334-353.

[7] Vassoler-Froelich, I. (2007). Urban Brazil visions, afflictions, and governance lessons. Youngstown, N.Y.: Cambria Press.

[8] Rabinovitch, J. (1996). A Success Story of Urban Planning: Curitiba. Scientific American). (Reprinted in Cities Built for People, U. Kirdar, 1997, New York: United Nations)

[9] Brooke, James. (1992, May 7). "Curitiba Journal: The Road To Rio." The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com

[10] Gratz, R. (2013, Aug 6). Curitiba: An Environmental Showcase. Huffington Post. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/roberta-brandes-gratz/curitiba_b_3713953.html

[11] MacLeod, K. (2002). Curitiba: Orienting Urban Planning to Sustainability. International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives, Case Study 77. ICLEI-Cananda.

[12] Kemp, R., & Stepahi, C. (Eds.). (2014). Global models of urban planning: Best practices outside the United States. McFarland & Company.

[13] Irazábal, C. (2006). Localizing urban design traditions: Gated and edge cities in Curitiba. Journal Of Urban Design, 11(1), 73-96. doi: 10.1080/13574800500297736

[14] Polli, S., & Pilotto, A. (2009, August). Retrieved from http://www.fflch.usp.br/ centrodametropole/ISA2009/assets/papers/18.5.pd

[2] Macedo, J. (2004). Curitiba. Cities. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2004.08.008

[3] Suzuki, H. (2010). Eco2 cities: Ecological cities as economic cities. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

[4] Montaner, J. (1999). el modelo Curitiba: movilidad y espacios verdes, Ecología Política, 17

[5] Rabinovitch, J. (1992). Curitiba: towards sustainable urban development, Environment and urbanization, 4(2)

[6] Macedo, J. (2013). Planning a Sustainable City: The Making of Curitiba, Brazil. Journal of Planning History, 12(4), 334-353.

[7] Vassoler-Froelich, I. (2007). Urban Brazil visions, afflictions, and governance lessons. Youngstown, N.Y.: Cambria Press.

[8] Rabinovitch, J. (1996). A Success Story of Urban Planning: Curitiba. Scientific American). (Reprinted in Cities Built for People, U. Kirdar, 1997, New York: United Nations)

[9] Brooke, James. (1992, May 7). "Curitiba Journal: The Road To Rio." The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com

[10] Gratz, R. (2013, Aug 6). Curitiba: An Environmental Showcase. Huffington Post. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/roberta-brandes-gratz/curitiba_b_3713953.html

[11] MacLeod, K. (2002). Curitiba: Orienting Urban Planning to Sustainability. International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives, Case Study 77. ICLEI-Cananda.

[12] Kemp, R., & Stepahi, C. (Eds.). (2014). Global models of urban planning: Best practices outside the United States. McFarland & Company.

[13] Irazábal, C. (2006). Localizing urban design traditions: Gated and edge cities in Curitiba. Journal Of Urban Design, 11(1), 73-96. doi: 10.1080/13574800500297736

[14] Polli, S., & Pilotto, A. (2009, August). Retrieved from http://www.fflch.usp.br/ centrodametropole/ISA2009/assets/papers/18.5.pd