Evolution of the public transportation network

The beginnings

Figure 1. Streetcar. Source: Foreigners in Curitiba

Figure 1. Streetcar. Source: Foreigners in Curitiba

In 1887, horse drawn vehicles were the first form of public transportation to be established in Curitiba, and then electrically powered streetcars replaced these horses in 1912. From the streetcars introduction until the early 1950s they progressively evolved and were continuously upgraded (Figure 1). While the streetcars were on the roads, the first public and private bus companies emerged in 1928 and 1930 respectively, however there was a much larger proportion of people riding the lower priced street cars than the buses. Nevertheless, as Curitiba began to grow, buses became more convenient and beneficial due to their swiftness and flexibility and gradually replaced streetcars completely in 1952. In order to manage the bus system 10 bus companies were set up in 1954, each dealing with a particular area in the city. As Curitiba continued to grow and evolve, extensive conflict developed between the various modes of transportation in addition to the different companies operating them all because of the convergence of their routes especially in the central city. [1]

Curitiba did not have a working and effective transportation network, but instead an assortment of different systems that did not fit together. This disorder came about because each transportation company operated in their own area usually without networks linking to other areas. The lack of direction and regulations meant that there was no incentive to connect the whole city together and create a functioning transportation system. Companies were instead assigned to particular areas in the city, and their systems developed in response to the residential, commercial, and industrial regions within their district and not between other areas in the city. This also meant that the public transportation that did exist was frequently undependable and inconvenient. Additionally the city center was a main destination in all of the transportation networks, which exacerbated the traffic within the central area. [2]

A plan for Curitiba established in 1943 anticipated rapid growth in automobiles and consequential traffic, this laid the groundwork for wide boulevards that extended out from the city center. The large boulevards were created, but much of the rest of the plan to continue building for private automobiles never took shape. Instead city officials realized that this plan, along with the exponential growth that was occurring would prompt increased congestion in the city and hence approved of a new Master Plan in 1965. Curitiba would not grow disorderly in all directions but instead grow along linear corridors in an orderly and directed fashion. [3]

Curitiba did not have a working and effective transportation network, but instead an assortment of different systems that did not fit together. This disorder came about because each transportation company operated in their own area usually without networks linking to other areas. The lack of direction and regulations meant that there was no incentive to connect the whole city together and create a functioning transportation system. Companies were instead assigned to particular areas in the city, and their systems developed in response to the residential, commercial, and industrial regions within their district and not between other areas in the city. This also meant that the public transportation that did exist was frequently undependable and inconvenient. Additionally the city center was a main destination in all of the transportation networks, which exacerbated the traffic within the central area. [2]

A plan for Curitiba established in 1943 anticipated rapid growth in automobiles and consequential traffic, this laid the groundwork for wide boulevards that extended out from the city center. The large boulevards were created, but much of the rest of the plan to continue building for private automobiles never took shape. Instead city officials realized that this plan, along with the exponential growth that was occurring would prompt increased congestion in the city and hence approved of a new Master Plan in 1965. Curitiba would not grow disorderly in all directions but instead grow along linear corridors in an orderly and directed fashion. [3]

The 1965 Master plan

Figure 2. Structral Axes. Source: Curitiba, URBS

Figure 2. Structral Axes. Source: Curitiba, URBS

The exponential growth that was occurring in Curitiba during the 1960s, lead to a reassessment of the original plans that had focused on prioritizing automobiles on the roads. Instead there was a new focus in the city that concentrated on a transportation system that met the needs of all people as opposed to those who used private automobiles. The 1965 Master Plan originated from a public competition, with the successful plan being presented to the urban authority and then used to develop the planning policies. The plan created circumstances for the execution to be coordinated with planning policies at various scales so that there would be interconnectedness within the city of Curitiba. The main objectives of the Master Plan were to: decongest the central city area by building along the main corridors; control and manage the population; provide economic support by reducing the expenses of transport, trade, and exchange; improve infrastructure with emphasis on water, electricity, and sewage; and adjust the urban growth movement to a linear form through the use of the arterial corridors. Jamie Lerner the mayor at the time demonstrated political determination and expertise that was crucial in beginning and executing the city’s transportation plans. [4] [5]

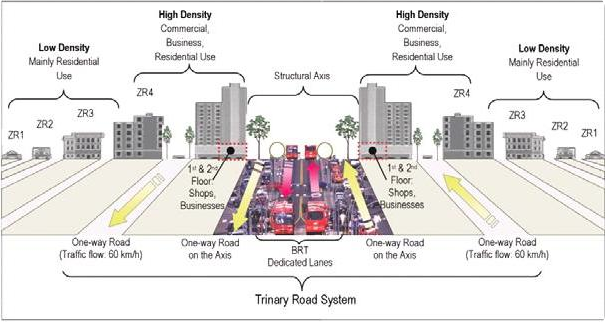

Figure 3. Trinary Road Systems. Source: Curitiba, URBS

Figure 3. Trinary Road Systems. Source: Curitiba, URBS

Curitiba’s Master Plan incorporated land use planning with the transportation system; this integration demanded a complete reorganization of the city. The plan for redevelopment consisted of structural axes that extend out from downtown (Figure 2); these axes direct the concentration of growth along the main roads, which in turn creates the concentrations required to make the public transportation network practical. These main transit axes are made up of a “trinary” organization of streets running side by side, where the central street is dedicated for “express buses” which move in opposite directions in addition to low-speed vehicles and parking. The parallel streets that are one block away in both directions are one-way streets that direct high-speed traffic (Figure 3). The express buses that operate on the central streets connect with “feeder buses” at the end of the express busways. These feeder routes are linked to the surrounding neighborhoods and connect residential areas to the main central bus system. Additionally, “inter-neighborhood routes” make it possible for travelers to go between neighborhoods without having to go to the city center first making it much more convenient and accessible. Some other routes that exist within the bus system include conventional routes, city center routes, night routes, and pro-park routes. [2] [4] [6]

Bus Tubes

Figure 4. Tube Stations. Source: Inhabitat; Transportation Tuesday Curitiba

Figure 4. Tube Stations. Source: Inhabitat; Transportation Tuesday Curitiba

After the express bus system was introduced there were delays with passengers getting on and getting off the buses, creating interruptions to the system. As a result they introduced tube stations at each stop where passengers paid their fares in raised boarding stations before boarding buses, which significantly reduced boarding times. Additionally they had specified doorways for boarding at one end and for disembarking at the other end which created less disorder between the passengers. Passengers wait within these tube stations for the buses on a raised platform at the same height of the bus, this easy access at the same level allows for disabled passengers, the elderly, and those with strollers to easily get on and off the bus without added trouble (Figure 4). [4] [7]

Bus fares

Throughout the bus system, passengers are only required to pay a single fare and are allowed unlimited transfers where the bus system interconnects. Transfers would occur within the already paid sections of the bus terminals so there is no confusion with who has and hasn’t paid. This flat fare system reduces confusion, time, and costs, as passengers no longer have to buy a ticket for each ride that they are taking which is beneficial to all passengers and especially those of lower incomes who generally require more transfers and have fewer funds available. Since 2002, there are now smart cards available so that passengers can just upload money onto their card and swipe it each time they enter the bus network which is much more practical. [3] [8]

bus vehicles

Figure 5. Bi-Articulated Buses. Source: Curitiba, URBS

Figure 5. Bi-Articulated Buses. Source: Curitiba, URBS

The bus vehicles also vary depending on which route they are taking, with the express buses carrying the highest number of passengers on the main structural axes and feeder buses carrying a smaller number of passengers along the inter-district routes. Bus sizes and frequency depends on the passenger demand and fits with their specified routes. Buses on the main express routes used to have a capacity of 110 passengers however with increased demands the buses were then changed to articulated buses which could hold 170 passengers. Since 1991, bi-articulated buses were introduced which are much longer and comprise of two pivot points so that they can get around bends, these buses can hold up to 270 passengers increasing the capacity of passengers who can be moved (Figure 5). By adjusting to fit demand, the buses meet the specific requirements for each route and this decreases the amount of empty buses on the streets that would otherwise be wasting energy, resources, workers, and money. [7]

management/bus companies

The transportation network in Curitiba has always been split into the various areas of the city with each area managing its own bus company. These separate entities made it much more difficult to operate because of the difficulty in coordinating the unconnected divisions, and making sure that the buses worked as a unit. However this all changed in 1990 when the introduction of the Urban Development Authority of Curitiba (URBS) was assigned to design and manage all modes of transportation. While there are still individual bus companies that make up the city, URBS role is to assure that the entire transportation system works in unison with one another and together with urban planning developments. [8]

Shift from automobiles to buses

The success of Curitiba’s Bus Transit System has accomplished a shift in travel routines, where the majority of the city’s population has altered their travel modes from that of the automobile to buses. According to survey results that were done in 1991, the establishment of the Bus Transit System has reduced about 27 million automobile trips and 28 percent of car users have changed their transportation means to the bus. The predominant population of Curitiba receives low wages and transportation can be expensive for these individuals. However, because of the single fare system, transportation prices are reduced and now majority of the workers now use the public transportation system to get to and from work each day. This shift towards buses has decreased congestion on the streets, reduced traveling times, and increased accessibility, with these changes the city has been able to create more pedestrian areas making it much more convenient for the public to use and move around. [3] [6] [7]

Green line (6th Corridor)

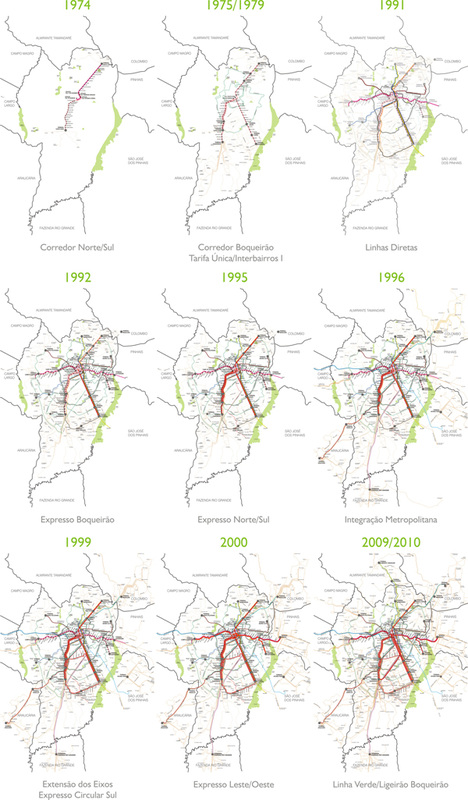

Figure 6. The Evolution of Curitiba's Public Transportation Network. Source: Curitiba, URBS

Figure 6. The Evolution of Curitiba's Public Transportation Network. Source: Curitiba, URBS

Curitiba’s transportation administration has been continuously improving the bus transit system since its establishment and the most recent addition to the network is the sixth corridor, which has been named the Green Line (Linda Verde) (Figure 6). Building operations began for the Green Line in 2009 and it is the first corridor to include overtaking lanes for various bus services. This entails that bus stations and streets can include a combination of bus services because stations are spacious enough to include buses on either side, and roads are wide enough to have passing lanes for buses to overtake. The buses that operate on the Green Line run on 100 percent bio-diesel and it is estimated that there is a reduction in emissions produced at around ‘30 percent less carbon dioxide and 70 percent less smoke’ (pg. 281) compared in contrast to buses that run on traditional fuel. The constant improvements that have been integrated into the bus rapid system with the advancement of corridors and environmental transformations portray Curitiba’s dominance in transportation innovation over the last 35 years. [8]

environmental and quality of life impacts

Curitiba’s public transport system has received a great deal of recognition for its strategies that have improved the environment and quality of life, through its reduction in emissions and resources used in the city. In order to be environmentally conscious a city must reduce the amount of waste that it produces and preserve the maximum amount of resources. For Curitiba this meant that it needed to make improvements with their existing transportation network instead of trying to start from scratch and build a rail network. As a result Curitiba chose to focus and expand its bus system, because that is what they had. The implementation of the system was done in small steps so that the impact on the environment and quality of life could be assessed and adapted according to its impacts on the city and people. [4]

Lessons that might be applicable elsewhere

Figure 7. Trinary Road System. Source: Boise Planning; Trinary Road

Figure 7. Trinary Road System. Source: Boise Planning; Trinary Road

The success of Curitiba’s Bus Transit System has been observed globally and as a consequence many cities and planning officials have looked towards Curitiba to see whether they can try and apply similar establishments to their own cities. One of the most fundamental lessons that was viewed in Curitiba was the importance of understanding how public transportation is connected with land use planning and economic development. Having a fundamental understanding of these features in a city and how they work together is crucial in order to develop an effective plan that can promote urban growth, development, and improve the lives of the community. As Curitiba was planning their new transportation network they knew that the ‘origins, destinations, and transportation routes and modes’ (pg. 17) must be taken into account in order for the transportation to be beneficial in moving people to and from their places of residence and other frequently visited destinations. If these locations were not easily accessible to transportation routes then the whole system would be impractical. What can be viewed from the land use planning is that the buildings along the public transport routes are of greater density whereas the further you move away from the routes the buildings are of lower density and are typically made up of residential neighborhoods (Figure 7). Furthermore, from the beginning, Curitiba recognized that they had limited funds to develop the network and therefore had to use what was accessible and compatible with their plans. Therefore, they began to develop a bus network instead of an underground train system because they already had buses and to build an underground system would be time consuming and costly. [5] [7]

These basic principles can be applied to other cities in order to help improve their public transportation systems in conjunction with city planning as a whole. However, it must be addressed that the effectiveness of particular transportation modes and networks will be different in every city and is not necessarily comparable. These dissimilarities can be due to differences in the geography of the land, where some cities have been built in mountainous regions and others across flat spaces. Population densities are also an important factor, some cities might be densely populated whereas others are sparsely populated and much more spread out. Consequently these distinct geographies indicate that transportation networks will vary depending on particular circumstances. In addition to geographical features, the financial resources and available technology are also important in determining what transportation networks are affordable and can be built. On the whole, Curitiba’s approach to planning a public transportation network has been extremely successful and the key lessons learnt are definitely applicable elsewhere. Nevertheless, it is important to understand that the exact same development may not be applicable in all cities because cities differ in their geographic, demographic, and financial characters. [1]

These basic principles can be applied to other cities in order to help improve their public transportation systems in conjunction with city planning as a whole. However, it must be addressed that the effectiveness of particular transportation modes and networks will be different in every city and is not necessarily comparable. These dissimilarities can be due to differences in the geography of the land, where some cities have been built in mountainous regions and others across flat spaces. Population densities are also an important factor, some cities might be densely populated whereas others are sparsely populated and much more spread out. Consequently these distinct geographies indicate that transportation networks will vary depending on particular circumstances. In addition to geographical features, the financial resources and available technology are also important in determining what transportation networks are affordable and can be built. On the whole, Curitiba’s approach to planning a public transportation network has been extremely successful and the key lessons learnt are definitely applicable elsewhere. Nevertheless, it is important to understand that the exact same development may not be applicable in all cities because cities differ in their geographic, demographic, and financial characters. [1]

References

[1] Rabinovitch, J. & Hoehn, J. (1995). A Sustainable Urban Transportation System: The “Surface Metro” in Curitiba, Brazil.

[2] Vassoler, I. (2007). Urban Brazil: Visions, Afflictions, and Governance Lessons. New York: Cambria Press.

[3] Goodman, J., Laube, M., & Schwenk, J. (2006). Curitiba’s Bus System is Model for Rapid Transit. Race, Poverty, & the Environment. 12(1), 75-76.

[4] Rabinovitch, J. (1992). Curitiba: towards sustainable urban development. Environment and Urbanization. 4(2), 62-73.

[5] Rabinovitch, J. (1996). Innovative land use and public transport policy. Land Use Policy. 13(1), 51-67.

[6] Macedo, J. (2004). Curitiba. Cities. 21(6), 537-549.

[7] Rabinovitch, J. (1995). A sustainable urban transport system. Energy for Sustainable Development. 11(2), 11-18.

[8] Lindau, L.A., Hidalgo, D., & Facchini, D. (2010). Curitiba, the Cradle of Bus Transit. Built Environment. 36(3), 274-282.

[2] Vassoler, I. (2007). Urban Brazil: Visions, Afflictions, and Governance Lessons. New York: Cambria Press.

[3] Goodman, J., Laube, M., & Schwenk, J. (2006). Curitiba’s Bus System is Model for Rapid Transit. Race, Poverty, & the Environment. 12(1), 75-76.

[4] Rabinovitch, J. (1992). Curitiba: towards sustainable urban development. Environment and Urbanization. 4(2), 62-73.

[5] Rabinovitch, J. (1996). Innovative land use and public transport policy. Land Use Policy. 13(1), 51-67.

[6] Macedo, J. (2004). Curitiba. Cities. 21(6), 537-549.

[7] Rabinovitch, J. (1995). A sustainable urban transport system. Energy for Sustainable Development. 11(2), 11-18.

[8] Lindau, L.A., Hidalgo, D., & Facchini, D. (2010). Curitiba, the Cradle of Bus Transit. Built Environment. 36(3), 274-282.